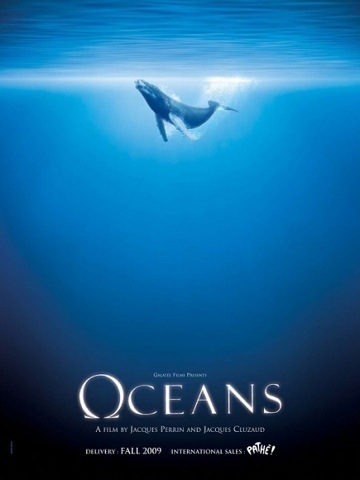

Oceans, an epic adventure for Luc Drion

- by Luc Drion

Five years in the making, Oceans is a film that mixes documentary and fiction to bring the wonders of maritime life to the big screen. Luc Drion talks about his work on this epic undertaking.

What is the film about?

I would like to let Jacques Perrin explain who sums it up quite well:

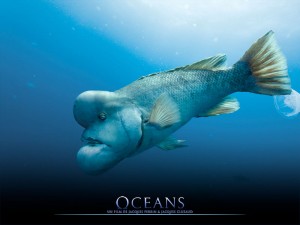

“ Drama and documentary mixed, Oceans is a meeting with animals of the sea, the men who live by them and those who exploit them. An unique testimony of the fragile beauty of a world about to disappear. A recent study published in Science magazine, predicts that at the current rate we exploit it, the main part of marine life will have disappeared by 2048. We talk about the sea as a resource. But resources dry up when badly managed. In order to fish for one creature we catch 20 others. For no reason what so ever. Every year millions of fish get thrown back in the water, dead or almost. I just want to reach out to people. To draw their attention and memories by means of emotions. One has to leave the film saying that we cannot let it happen, that we do not have to let all these creatures disappear. All this wealth that is still being ignored.”

“ Drama and documentary mixed, Oceans is a meeting with animals of the sea, the men who live by them and those who exploit them. An unique testimony of the fragile beauty of a world about to disappear. A recent study published in Science magazine, predicts that at the current rate we exploit it, the main part of marine life will have disappeared by 2048. We talk about the sea as a resource. But resources dry up when badly managed. In order to fish for one creature we catch 20 others. For no reason what so ever. Every year millions of fish get thrown back in the water, dead or almost. I just want to reach out to people. To draw their attention and memories by means of emotions. One has to leave the film saying that we cannot let it happen, that we do not have to let all these creatures disappear. All this wealth that is still being ignored.”

How much time was needed make the film from start to finish?

When I came onboard at the end of 2004 as a consultant to help the construction of the stabilized remote head, the production had already been working on the project for two years developing the script and raising funds. My first day of shooting was in may 2005 on the “sardine run”. It was a test shoot aboard a zodiac off the coast of South-Africa, using lightweight equipment such as a handheld Arri 435, lightweight zooms from century, a series of primes and a helicopter shoot using Stab-c. At the same time special equipment was being developed under the guidance of Olli Barbé, director of developments, a position unknown to me until that time. We also did a lot of tests with the stabilized head Thétys both on the sea as on land using a crane. And we also needed to modify the mini helicopter Birdy-fly to be able to shoot in super35, using an Arri 2B and Zeiss 2.1 lenses in pl mount. We started using our camera systems on location in may 2006 and continued shooting until the end of 2008. The editing started in september 2008 and took about a year, following the immense task of selecting the rushes on a daily basis. A total 490 hours of rushed had to be reviewed. Post production started with creating the digital effects after the production wrapped the fictional part of the shoot in october 2008. And finally the DI was performed over period of sixteen weeks in 2009.

And what was the budget on this kind of project?

Enormous !

Was this you first collaboration with director Jaques Perrin ?

No, we had worked together before on “ le peuple migrateur”, which he co-directed with Jacques Cluzaud. We first met when he was producing “Himalaya, l’enfance d’un chef” for director Eric Valli.

What was the directors vision in regard to the look of the film?

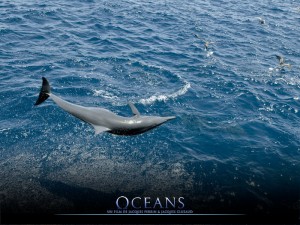

From the start the idea of the two directors was to be as close to the animals as possible by moving with them. They favored shorter focal lengths to get the viewer in the center of the action, and give them a feeling of life and movement: “ being a fish among the fish and not a spectator”, was their motto. The film was conceived as a drama and not as documentary. The same approach was used for both the underwater and the above the water footage. Special care was taken to not feel the mechanics involved in the process of making the film, like vibrations of the boat or helicopter. So stabilization of the cameras was an important issue on this film.

What were the shooting and projection formats you used?

From the start we decided that the projection format for the cinema would be 2.40, but protecting it for 1.77 with the possible release in Imax 70mm in mind. Tests had been done by Arane and it came out really well. Also a tv version in 1.77 was released.

The choice of shooting formats both above and under water became clear very quickly. There wasn’t much discussion as to what format was suited for the exterior shoot, certainly not at that time in 2005. 35mm was the only option, also because we were planning to shoot a lot of slow motion. Depending on the type of shots we used both 3 and 4 perf super35. For the underwater footage it quickly became clear that it had to be a digital acquisition because of its greater autonomy : 48 minutes of shooting time compared to 6 minutes in 3perf S35. For Phillipe Ros, DOP and image technical supervisor, the choice what digital camera to use was based on a simple concept: give the colorist digital captured images that represent the most an image scanned from a 35mm negative: images that have a softer contrast and a lower chroma level allow the most information to be captured. In 2003 the only camera who met all our criteria in a shooting friendly economical package was the Sony HDW-F900/3. The cameraman responsible for the underwater shoot, Didier Noirot, preferred that the underwater housing and the camera did not weigh more than 45 kilos. The housing was build by Jean-Claude Protat from Subspace, a company based in Geneva. The F900/3 was the first camera to use the hyper gammas created by Christian Mourier of Sony, and for this film Olivier Garcia created a user gamma that also could be used. These gamma curves allowed to capture images with a softer contrast, similar to a scanned image, besides having the advantage of capturing a wide dynamic range. Which helped the underwater cameraman a lot as he was not able to use any zebras or waveform during the shoot.

With the aid of colorist Laurant Desbruères and the postproduction supervisors Tommaso Vergallo and Juan Eveno of Digimage Cinéma, Philippe Ros created a workflow based upon improving all the steps in the digital chain. None of this would have been possible without the support of executive producer Olli Barbé, willing to take a step in the digital world and start a year long research in digital development. The goal was to work for a maximum of quality, usable for projection on big screens wether the captured image was digital or on film.

Based on test shoots, the ‘ vision’ DIT crew led by François Paturel, assembled a set of 13 cameras which included the sony HDW-F900, HDC 950 and F23. This crew did not dive, but assisted the underwater cameramen in the zodiac, helping them prepare and check the rushes. A program created by Christian Mourrier allowed to choose among 5 gamma curves and 5 scene files, controlling the multi-matrix by lowering color saturation or adjusting the sharpness in relation to the visibility under water. Two thumb wheels situated on the housing allowed for a selection of 25 settings. Besides these setting Philipe Ros proposed Galatée to implement a concept of digital emulsions, allowing the operators to intervene in the digital workflow. The recording of these selections on the audio track via another program created by Christian Mourrier allowed the cameraman, DIT, colorist and post supervisor to check and improve the recording choices during the production period.

What film stocks did you use?

In 2005 we did a lot of key-light tests of the different stocks that were on the market. Afterwards we analyzed them watching a classic film-print and an HD telecine at Digimage. After the results were analyzed by Philippe Ros, responsible for the workflow, and the post production crew we chose the Kodak 5201 and 5205 as our exterior stock. Luciano Tovoli used the 5218 as his stock for the drama portion and for some of the underwater shots done on 35mm we used the Fuji F-64D and the Kodak 5205.

Different cameramen were responsible for their own piece of the film. How did this work?

Different crews were assembled depending on the equipment used and the sort of imagery that had to be shot. I was responsible for the regular helicopter shots, among others the storm sequence. I also did the shots using the Thétys stabilized head on the boat and some of the shots on land. And I operated the drama scenes on which Luicano Tovolli was the DOP. Frédéric Jacquemin was the pilot of the mini helicopter Birdy Fly and Christophe Pottier was the camera operator.

Laurant Fleutot also helped on different sequences: salmon and the storm in the Philippines. Laurent Charbonnier and Thierry Thomas were able to put their experience in wildlife cinematography to good use for among others the scenes of the predation of the turtles and sea lions. To harmonize the work of the different cameramen with what Phillipe Ros and camera assistant Stéphane Aupetit were doing, a check list was made with precise instructions that had to be followed for the test shoots and the actual production. These procedures were drawn up with the idea to always follow and check the digital workflow in collaboration with the colorists of Digimage. For the underwater work the shoots were organized from the start by Didier Noirot and René Heuzey. They were joined by seven operators of different nationalities. In the same way Philippe Ros started a work schedule for the underwater shoots in order to harmonize the work of the cameramen. There was also a checklist for testing the digital cameras and analyzing of the rushes by the vision crew. All the information about the cinematography was posted on a website and could be consulted by members of production, editing, lab and telecine.

How were the different cameramen able to communicate with the directors?

Because of the great number of shoots that took place at the same time, the directors could not always be present. Personally I did a lot of filming with one of the directors Jacques Cluzaud aboard a helicopter or using the Thétys. When we went out on our own we prepared the shoot in Paris with the directors, leaving them with set of precise instructions about the animal presence and other different circumstances concerning the type of shoot ( bad weather). In Paris, Jacques Perrin was often the first to view the rushes and judge them, not taking the local difficulties into account, on their quality and content. So he could guide us towards getting the right images.

Did you use any special equipment to make the images above the water?

To be as close as possible to the animals above water and at their speed ( 18 nodes for the dolphins) the use of a stabilized head was a necessity. As the existing ones ( Scorpio, Flight head etc) were not build to be used on the sea and not always available, Galatée decided to build his own. It was Jacques-Fernand Perrin, an ex military engineer, who designed it and Alexander Bügel build it. He was also the grip on the shoot. Jacques-Fernand Perrin came along to adjust the settings of the head in order to have the maximum of stabilization in relation to the conditions of the sea or the type of boat. The Thétys head was fixed atop or underslung on a crane that was build to fit the zodiac. It could be folded for transport and in case of bad weather. After some time of adjustments the Thétys did good at stabilizing with little drift. The movement of the horizon caused by the roll movement of the boat was difficult to adjust. But in the end the building of the head was a good financial investment considering the amount of shooting days it was used on and the amount of shots that are in the film.

For practical reasons ( Thétys and the crane weigh 800kg) and economical (the transport costs were outrageous ) we used existing gear on shoots where good stability was less important. We also used two types of stabilized platforms that worked on 2 axes. The Perfect Horizon that came with a technician, simple and effective. And also the Makohead, which came without a technician but was more difficult to adjust and less effective. We also build camera housings in aluminum outfitted with rain deflectors ( spinning portholes) for the storm sequence. They were attached to the boat to cover multiple angles.

For a sequence that required us to lift out of the water during the shot aboard a moving ship The Bounty, we relied on the Hydrohead system; a well known housing fitted with a submersible remote head attached to a crane.

For the helicopter shots we chose to use the Stab-c stabilized head, because it was at that time the best adapted and the most widely available at multiple rental locations on all continents. There were two models. We tried, if possible, to use the “ Super G” because it is equipped with stronger pan and tilt motors .

What type of cameras did you use?

Both the 35mm cameras and digital camera package for the underwater work, were rented from Panavision Paris. I worked a lot with the Arri 435, but we also used some Arri 3’s and Aaton 35’s. The variable speed control RCU was used a lot to quickly adjust the camera’s speed depending on the action we were filming, mainly in the variable speed/ shutter configuration. This allowed us to be always in sync with the action. Often we filmed two different actions during a take: fast jumps and slower behavior of the animal that each needed to be filmed at different speeds. The RCU allowed us to instantly change the speed and adjust the exposure automatically. To review the captured footage we had an Easylook, a compact and robust hard-disc recorder, that allowed us to view the shot in slow-motion. It also had the huge benefit that it automatically started recording in sync with the camera.

Concerning the lenses we used almost every available lens: the Angenieux and Zeiss zooms, the lightweight 15,5-45 Zeiss for handheld work, and also Master, Ultra and Cooke S4 primes. For helicopter work we used the 17-80 Optimo for landscapes, the 30-300 Angénieux T4.5, an old 25-250HR that was adapted by Laaziz Kheniche of Panavision to cover 1,77 in super35, which was chosen for its light weight in the helicopter. On the Thétys we started out by using the 17-80 Optimo, but as Jacques-Fernand Perrin was able to make the head more stable over time we were able to switch to the 24-290 Optimo. For the drama part Luciano Tovolli had chosen the 15-40 and 24-290 Optimo, next to a set of Cooke S4’s.

Was there any special equipment developed for the underwater work?

Several. Besides the Galatée housing, Jonas, Siméon, the polecam, the studio housing and a microscope were developed under the direction of Dimitri Billecocq, head of developments and Phillpe Ros, head of digital cameras development. Jonas, Siméon and the polecam were build around a capsule or a small housing fitted with a small sensor removed from a sony HDC950 ( HKCT950) and a Zeiss 6-24 zoom lens. The capsule was linked to the camera via a fiber optic cable that was not only able to transmit the images but also allowed to command the zoom, focus, aperature, filters functions during the filming process.

Jonas: the capsule was placed in a controllable torpedo Jonas allowing to move backwards through a school of fish. The torpedo underwent a long period of testing in a navy tank used to test submarines, in order evaluate its hydrodynamical capacities.

Siméon: Alexander Bügel, key grip and constructions, made the system even simpler with a smaller torpedo.

Polecam: in this shape the capsule was placed inside a maneuverable sphere hung to the side or the back of the boat. Submerged it could dolly sideways or backwards with groups of dolphins at speeds up to 40km/h. Crank wheels allowed the operator to finesse the framing. In all these three configurations a device managed all the choices made by vision operator Matthieu Lamand, who’s a specialist in its use.

Studio housing: was build to improve the Galatée housing and allow the use of an external monitor both on land and in the sea. The small housing named Game Boy contained a 9” hd Transvideo monitor and a remote focus and aperature controller. Underwater moves using long zoom lenses also became possible, the underwater focus-puller could freely zoom to check the focus.

The microscope: starting from a Zeiss V20 stereo microscope by using one channel an adaptation of the table was made in order to be able to follow the animals in a drop of water using the crank handles. The realignment of the table in X,Y and roll, combined with the zoom of which the aperature ramping was corrected, allowed for movements of ½ mm to 20 microns.

A part from the company Developtim in charge of the controls of the capsule, the companies Télécast an Le Team helped in de development of Jonas. HD Systems under the direction of Nicolas Pollacchi and the technical supervision of Hervé Theys and Olvier Garcia had worked on the development and improvement of the capsule, the studio housing and the microscope.

How was your crew assembled?

Throughout the production I used the same assistant, Stéphane Aupetit who was very busy: reloading as there was no place for a loader, maintaining the cameras and lenses ( humidity and salt), solving a lot of connectivity problems ( bnc, zoom focus iris control) and mostly pulling focus. Not as easy on the sea as one does not have any references to judge distances, and you have to be able to react to short and sudden actions.

Thétys creator Jacques-Fernand Perrin joined me to keep the head in good working order and to adjust the stabilization levels. He had also written a program that simulated the vibration frequencies in order to better adjust the stabilization software depending on the condition of the sea and characteristics of the boat on which the head was attached to. The grips on board also helped to build the head: Alexandre Bügel, Edgard Raclo and Guilhem De Gramont. As we were using a crane two manned the arm and one the head. As this was a prototype they had to be able to fix it onsite. In the last year of production 2008 we had a lot of problems with the electronic amplifiers, broken motor sprockets. But they always managed to fix it and we never were unable to continue filming because of technical malfunctions. The skipper had an important task as he transformed the boat in a dolly and his knowledge about the animals has helped me a lot during the shoot. I mainly worked with Bernard Deguy and Alain Carpentier.

For the helicopter work I used local pilots at the different locations. And once again it became clear to me that the flying skills had an influence on the outcome of the images. In France the experience of pilot Thierry Leygnac was invaluable to get the strong images we got in those harsh conditions ( force 10) during the storm sequence.

Did you encounter any specific technical problems?

The shoot was a 3 year exploration, we constantly strove to get a more stable image. To achieve this we pushed the gain of stabilizers to its maximum. In doing so I noticed on some long shots a loss in definition. Which was probably due to frequencies that resonated between the stabilization motors and the lens/gate. This phenomenon resulted in a higher number of shots that were out of focus. This was evidently even more problematic when using shorter lenses, which was confirmed once we scanned the negative to 4k. I also encountered a problem that was new to me: ramping. On some zoom lenses used on the long end and at the widest aperature, the center of the image is at a different exposure level than the edges ( about a stop and a quarter). The result looks like an iris effects and is mostly visible on low contrast images (a grey sea).

During those four years we worked with three different labs and we were able to study the variations in quality between them. Arane-Gulliver in Paris carried out most of the development and it was a good choice.

The rain deflector of the Thétys was its Achilles heel. We spent a lot of time finding the right ones. Finally at Sea Marine in the USA we found one that had a reasonable weight and a good balance of the turning window ( vibrations). That said, it still was a fragile piece of equipment. It was not made to work 6 hours a day for long periods of time, so we broke a lot of motors and straps. For the regular helicopter work we spent a lot of time finding the right configuration. We started out with a 14kg 24-290 optimo zoom and 120m loads, but we had a lot of problems with vibrations using this setup. So we opted to use a lighter lens the Angénieux HR30-300 and 300m loads. The lens was an old generation HR25-250 that was adapted to S35. The Stab-C which is pretty powerful, but with the older generation of electronic sensors the fine tuning of the head and the gains by the technician was primordial. It also caused problems with the artificial horizon, so much so that the assistant besides his other duties had to constantly adjust it. We were not able to mount the rain deflector on the Stab-c. So for the storm sequences we used a short horizontal bracket that allowed the assistant to clean the lens in between takes. When the camera was mounted on the front of the helicopter, the position that offers the widest shooting angle, we had no access to the lens.

To have film travel across the world and going to ever more frequent x-ray checks, demanded a good organization by the production and the shipping agents. In the four years we only had one problem with the rushes, one should never transport film in ones luggage on a commercial flight. I was pleasantly surprised by the reliability of the Arri 435, which held up well under the violent chocks caused by sea travel and the constant humidity. On the contrary the zoom, focus, iris remotes, it did not matter what brand they were, were very fragile and we used up a lot of them!

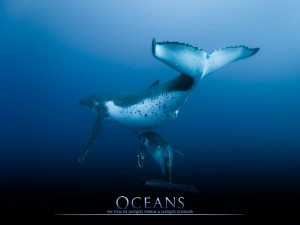

Did you use any special effects ?

Yes we did, for the drama part that was shot by Luciano Tovolli, Christian Guillon of L’Est was responsible for them. He also worked on the scene at the museum of extinct animals at Cherbourg, which is a mix of live action on green-key, real sets and 3D animation of large animals and 3D sets. He also composited the launch of the Ariane rocket on the Galapagos images and the long camera lift up starting with the wild sea and digitally ending up with a 3D satellite. As Jaques Perrin did not want any of the animals to be badly treated during the shoot, the scene featuring the massacre was done with animatronics. For the animals in fishnets and the fishing shark, Australian technicians were called upon for their extensive experience in underwater work and their stock of animal animatronics. Jacques Cluzaud, co-director, and Christophe Cheysson, 2° unit director, have spent a month in australia with Australian cameraman Simon Christidis shooting underwater footage on 35mm. Another example: the harpoons shot at the whales were deliberately rendered in naive way in order to make it less real.

How did the post-production come about, who was in charge?

The post-production was done using a 4K DI derived from 6K footage scanned from the 35mm negative, the HD footage was used natively. The grading took place on a 4K Da Vinci Resolve at Digimage and was performed by Laurent Debruères, under guidance of Luciano Tovolli, Philippe Ros and the directors. Thommasso Vergallo of Digimage was responsible for the scan and the shoot. The digital internegative and DCP were done at Digimage, the copies for evaluation at Arane, and the distribution prints at Eclair.

Would you use the same equipment today as you did in 2005 ?

Between 2005 and 2010 a lot has progressed, mostly in the field of digital acquisition. The autonomy of recording and the possibility to have a loop recording would be a huge advantage, but would the digital cameras be as reliable as an Arri 435 in extreme conditions on the sea. Today in 2010, based on the experiences I had, I would consider using a digital camera for its greater autonomy in helicopter work. The problem of not having variable speed seems to be resolved with the Arri Alexa, which is able to shoot from 1 to 60 fps. Cameras like the Genesis, D21, F35 and F23 ( thanks to user gammas) allow you to get good results because they have a good exposure latitude of more than 10 ½ stops. The Phantom camera which on paper seems great because of its slow-motion and loop recording possibilities could be a solution for precise shots like the jump of a shark, a very short action shot at 100 fps, but it lacks exposure latitude: only 4 stops. That said for shooting on the sea using the Thétys, 35mm seems for me still to be the best solution. The reliability, the exposure latitude and the small crew are still a plus today. A new gyrostabilizer head for helicopters made by Pictorvision seems to be interesting. The Eclipse has a real artificial horizon guided by GPS and excellently stabilized, comparable to Cinéflex. And thinking of what we could do using 3D today, that’s a whole different story.

What will happen to all the footage ?

We shot a lot: 490 hours of footage; 2/3 in hd and 1/3 in 35mm. The length of the film is 1h45min so that makes for 55% in hd and 45% in 35mm. There is still a lot of footage that is unused, it will be used for a tv series and as an image bank. Besides this I am happy to have shot 35mm. The images will be a witness, a timewhatch of 2008 that my children and their children can look at thanks to the archival capacity of 35mm. The HD footage raises some questions as to how and where to preserve the information. This is only the beginning of a problem which will grow with the wave of digital acquisition.

How did you experience the shoot?

The hardest part in the genre of nature films is to convey the visual impression of our eyes, which are very powerful, with the help of a camera which is just a tool. I have seen some extraordinary things such as the sardine run, the bubble net feeling or just a baby seal that came to say hello to us. All these fleeting moments should have been preserved on film. My apprehension of these situations was one of a fiction cameraman, I previsioned images in my head, based on the requests of the directors and I treated the animals as if they were actors. I operated with precise images in my head, dreams. From time to time it worked. It allowed me not surrender to much to the pressure of the unexpected. I was more looking for precise shots than to wait for them to just happen.

As a general conclusion I would say that the film was a great human and technical adventure and the hardest part was to stop having it. The different encounters across the world with scientists, technicians, the breton fishermen and local guides that thanks to their different cultural backgrounds gave me a different vision of the world. It was also an initiation voyage, a search for ones self and ones origins: to see twenty whales jump out of the water before you evokes a shock that takes us back to our origins and a kind of search for “ the mother” of the sea.

Now the film is released I hope that the images collected between 2005 and 2009 will provoke a reaction from the audience and the political powers to save what is still left in the oceans. It is not to late but it is urgent to change our ways and save the fauna and flora , and to save ourselves.

I would like to thank Jacques Perrin and Jacques Cluzaud for giving us the time and means to create these images, and also the team from Galatée Films.

interview by: Pierre Gordower

equipment links:

crew list:

Principals

Producer – Director: Jacques Perrin

Co-Director: Jacques Cluzaud

Production Manager: Olli Barbé

Production company: Galatée films

Underwater Cinematographers

Didier NOIROT

René HEUZEY

David REICHERT

Okumura YASUSHI

Simon CHRISTIDIS

Eric BÖRJESON

Jean-François BARTHOD

Thomas BEHREND

Mario CYR

Denis LAGRANGE

Directors of Photography

Luc DRION,SBC

Luciano TOVOLI, AIC, ASC

Philippe ROS

Christophe POTTIER (mini-hélico)

Laurent FLEUTOT

Laurent CHARBONNIER (turtles, iguanas)

Eric BÖRJESON

Philippe GARGUIL

Thierry THOMAS

Michel BENJAMIN

Jean-François BARTHOD

Olivier GUENEAU (Jonas, Siméon)

Valérie LE GURUN

Still Photographers

Pascal KOBEH

Richard HERRMANN

Roberto RINALDI

Yves GLADU

Mathieu SIMONET

Julien SAMSON

Hideki ABE

Mathieu FOULQUIER

DITs

FRANCOIS PATUREL (Chief D.I.T)

CYRILLE LIBERMAN

LEONARD ROLLIN

SALOMÉ GADAFI

EURIEL ETEVENON

MATHIEU LAMAND

BENOIT TORTI

MELANIE DESAUTELS-GUEGAN

MANUEL HENRY

First Camera assistants

STEPHANE AUPETIT (Chief 1st Assistant)

ERIC BORNES

MARYSE CHARBONNIER

RODOLPHE SOUCARET

THIERRY TRONCHET

TONY CHAPUIS

MARINE DELCOURT

STEVE MOREAU

NICOLAS DESAINTQUENTIN

FRANCOIS QUILLARD

DAVID REINHARD

EDNA ROELOFSE

ANTOINE STRUYF

HDSystems

Nicolas Polacchi

Olivier Garcia

Herve Theys

SONY FRANCE

Christian Mourier: Engineer from Sony

France Hypergamma Designer, SF25 &

Metadata designer

Fabien Pisano : Engineer, HD trainer

EMIT

Trevor Steele : U/W traveling, Zeiss

dealer, Help on Technical Issues and Tests

BAND PRO

Gerhard Baier : Managing Director Band

Pro, Zeiss Digi Zoom provider, Help on

Technical Issues

Partners and providers

Panavision Alga Techno

Bandpro Munich: Gerhard Baier

Arri Münich: Thomas Popp, Marc

Shipman-Mueller

Subspace

Bogard S. A., Emit S.A.

Birdy Fly

Aaton

HDSystems, LoumaSystems

Transvideo

Transpalux

TSF

Consultimage, Developtim, Magic Hour

Le Team

Carl Zeiss Digital Cinema Lenses: Dr

Winfried Scherle, Helmut Lenhof

Carl Zeiss MicroImaging: Ulrich Kohlhass:

Engineer

Kodak

Fujifilm

Sony

Canon

Postproduction

Digimage Cinéma

Laurent Desbruères: Senior Colorist –

Manager of the colorist team,

Tommaso Vergallo: Digital Cinema

Manager

Juan Eveno: Chief Operating Officer

Arane / Gulliver

L’Est

Mikros Image

Buf Compagnie

Def2Shoot

CTM Solutions

Eclair Laboratoires

(editor’s note: there are many more people

who worked on this film, and we apologize

for missing so many contributors.)