Lost River

how to catch a monster

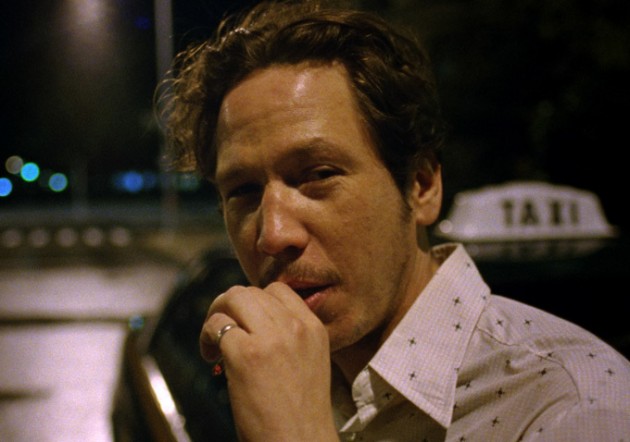

A fan of the universe of Gaspard Noë, star Ryan Gosling has availed himself of the services of Benoît Debie, SBC, to create the visuals on his first, strange feature-length film that oscillates between social fable and fantasy story. “Lost River” is one of the most anticipated films in the “Un certain regard” selection this year at the 67th Cannes Film Festival.

Interview conducted by François Reumont for the AFC and translated from French by Alex Raiffe.

What attracted you to this project?

Benoît Debie: Its unexpected side. The film begins on a very “social” and realistic tone with the story of a mother who lives in an economically devastated city (Detroit) and who barely gets by doing odd job after odd job to pay her bills and raise her children… and then gradually the film evolves into fantastic parallel universes that even I would call science fiction, and it was a super new experience for me to transmit this to the screen.

How did you get in touch with one another about this movie?

BD: I first met Ryan back in 1998. I happened to be in Los Angeles, and we met for a coffee. He already wanted to make a different first movie, but his busy schedule as an actor temporarily distracted him. We saw one another again in 2012 while I was colour timing Springbreakers, and then he had me read a new script – which was still being finished – but this time everything went much faster. The film was shot during the spring of 2013, produced by Marc Platt and Adam Siegel who had also produced Drive – very serious people.

How is Ryan Gosling as a director?

BD: Ryan is a pure cinephile. He has a solid visual universe, he cites many old films in black and white, with contrasting lights, things really made the old-fashioned way. As he has also worked with a lot of directors, one feels he has learned a lot from them.

Personally, he immediately told me he was a fan of Enter the Void and you find in Lost River some colours or influences from Gaspard Noë’s film.

Me, when I read the script, it made me think of Bill Henson’s photography. He is an Australian artist who works a lot on long exposures, and who takes portraits of young people or landscapes at night with a very dreamlike rendering. And when I showed him these pictures, he said, “that’s exactly what I want”. So we started aiming for blackness and darkness…

As I couldn’t really consider filming using long exposure, or play around too much with the cameras, I turned towards ultra bright lenses that allowed me to shoot in extremely low light conditions, and to recreate a certain nocturnal ambience. In order to achieve this, I managed to have lent to me the first models of the Hawk Vintage 1.0 series. When the film was shot in May 2013, there were only three available lenses (25, 40, 65mm) and they were still working prototypes for the German engineers. But we still went with them, and they allowed us to get a lot of images out of nighttime scenes.

What about the camera?

BD: The film is a true patchwork quilt! Personally, I am very attached to silver-process film and I think nothing has yet provided an adequate replacement, and I try most of the time to fight for every project to be filmed using real negative. This was again the case on this film, which was mostly filmed in 35mm, but there are some scenes we shot using Ryan’s Red Epic, including stolen shots or an underwater scene… The majority of the film was made with a Cooke S5 series, kitted out with the three Hawk 1.0 lenses, as well as a series of Russian anamorphic lenses I had already used on Springbreakers and that I mounted on the Red Epic. I love mixing formats and it is ultimately another artistic tool.

Didn’t Ryan expect to shoot the film using his own camera?

BD: Yes, of course he did! Ryan had bought the Epic in order to use it for his film. But as soon as we started talking, we exchanged our views, and he confessed that as an actor he was always a little bit lost on a digital shoot, especially because of the fact that the filmmakers never cut the camera… He felt that those never-ending takes were an obstacle to concentration on set. The feeling of rigorousness disappears… So he approved the choice of 35mm, and even beyond that, he was enough of a fundamentalist to forbid the on-set video assist! Finally after a few discussions, he consented to being supplied with a little Transvideo HF in order to check my framing, as well as one for the script supervisor who needed it for the inserts. But it was far from being the “video village” and the HD screen you now find on all digital films…

What about lighting?

BD: Ryan loves blackness… And I must say that as he did Harmony Korine – the director of Springbreakers – he pushed me pretty far from a photographic point of view. This was even more bold on his part because the film was shot using film stock and it was his first time directing.

Despite this, the producers gave us total freedom and nary a remark of the sort “Isn’t that a bit dark?” I nonetheless took a little safety margin for Ryan in order to avoid any disappointments linked to the enthusiasm of one’s first project, but I must say that the film is visually very anachronic compared to the average American production. To be frank, even compared to the films I made with Gaspard Noë, this one is even blacker!

What about processing the images?

BD: The film was shot in Detroit over a period of five weeks. As there hasn’t been a lab open in Detroit for a long time now, we sent the footage to Los Angeles. They were returned via FTP the very next day, it was very efficient! The colour timing was done at Company 3 in Los Angeles. This is a lab that does very big films… While I was colour timing, in the room next door they were working on Transformers and X-Men!

And I observed that coming to them with a little independent film was also a breath of fresh air for them… You are treated like royalty, and, frankly, the energy and personal commitment of the entire team are amazing. It was invaluable to us, and I don’t believe that the equivalent exists in Europe.

What about colour timing the images between the 35mm and the digital cameras?

BD: Comparing different productions I’ve worked on, I find that I always spend a lot more time colour timing a digital image than one generated by film. For example, I find myself calibrating a shot in which a fire truck passes by in the background with its lights flashing, moving from a very unrealistic mix of white colours to a mix of pink ones. The colour painter told me it is because the Epic’s sensor.

So you try to compensate, and to restore the image… In the end, if I spend fifteen minutes on a film image, I’ll spend twice as long on a digital one. But you’ve also got to admit that sometimes these strange reactions of the sensor truly serve the image. For example in the underwater shot filmed with Epic, the results were beautiful.

published with the kind permission of the AFC.