The broken circle breakdown

by Jo Vermaercke.

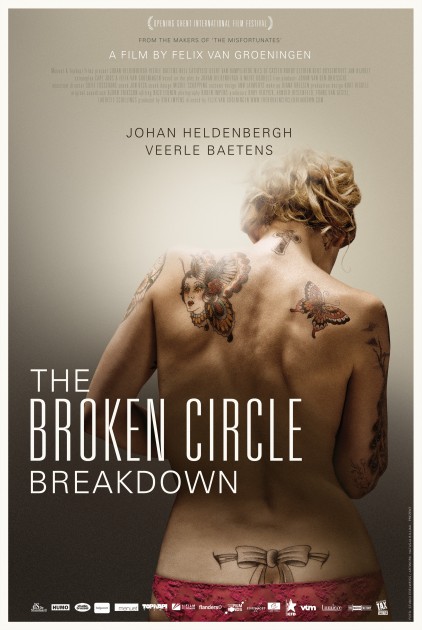

For his fourth movie, The Broken Circle Breakdown (2012), director Felix Van Groeningen once more teamed up with director of photography Ruben Impens. The movie tells the love story of Elise and Didier (Veerle Baetens en Johan Heldenbergh). They couldn’t be happier when their daughter Maybelle is born. However, when Maybelle turns six, she becomes seriously ill and her illness impacts Didier and Elise’s relationship. Both of them react differently to the diagnosis, but don’t have any other choice but to fight together for their daughter. The Broken Circle Breakdown was an enormous success and the movie won many international prices, one of which was a César for the Best Foreign Film. It was also nominated for an Academy Award in the category of Best Foreign Language Film.

How long have you already known Felix Van Groeningen?

We actually became friends quite a long time ago, when Felix was still studying at the art academy. I had already graduated from KASK (Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent) when he finished his final project, 50cc.Felix was a very dynamic person and everyone knew him. He was also engrossed with theater and Kung Fu and created remarkable things. We had a connection and he asked me to film his final project for school (academy). Originally, this movie was supposed to be a short film, but it was 40 minutes long when he finished it. The film was about young boys who hung out during a vacation and who tried to be cool with their 50cc scooters. This was something I identified with and I really wanted to shoot that. (laughs) Trixie Withley, Sam Lowyck and Lies Pauwels took part in the movie and Felix’s mother was responsible for the decor, which was very ambitious. We all came from Ghent, but found a piece of wasteland in the harbor area of Antwerp. There, he installed a fake gas station. He had also bought a trailer for a couple hundred euros that had to be moved from Ghent to Antwerp. When we drove to the set in the pickup truck of Felix’s mom, we passed the truck that carried our trailer. At that moment we all felt something great was happening, and that was a wonderful experience. Next to our set was a gypsy camp, with actual gypsies living there. We were worried they would trash our set, so Felix decided to sleep there. As soon as the trailer arrived, he stayed on set. He also did it to get a connection with the location. We camped there for about ten days.

The previous year he had made Truth or Dare, also for college, and that was a very intense project. The movie was about typical behavior of young people: taking of your mask, being yourself, stopping with posing and having the urge to score. But it had content and I was immediately intrigued by his work. That’s basically where it all began.

Do trailers often appear in his movies?

Yes, these refer to Felix’s roots, more specifically his hippie roots. In a way, his family is like gypsies: one half of the family lives in France, the other in Portugal.

So that was the beginning of a great collaboration?

Yes, although I did not realize it yet at the time. We filmed on two mini-DV cameras and we wanted to shoot plenty of material. I still had to learn all of that.

Was it possible to learn in that context?

It was and we also worked really hard. I think that if you start with an idea, you have to go for it. If you envisaged a car wreck in which a girl loses her virginity, then you need to look for the right car wreck. If it has to be red, you search until you find a red car wreck. Nothing happens by itself, you actually have to work for it.

That drive, is it still there?

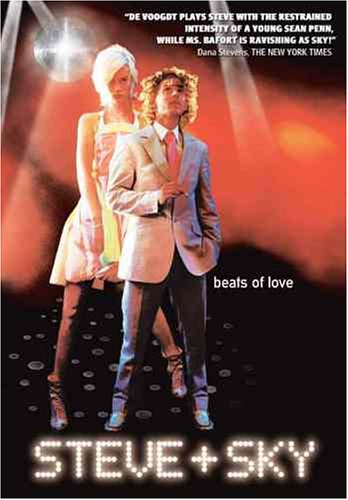

Yes, it is. Dirk Impens also met Felix at that time and he easily figured out how talented Felix was. In 2002, at 25 years old, Felix made Steve & Sky, which was our first feature film together. That was exceptional at those times. There were no digital cameras yet; everything was shot on film. It was a lot more difficult then.

Why did you choose Super 16 reversal?

That choice was based on test results. By the way, there weren’t many options and DV was the only format we already had experience with. I remember our tests at Studio Skoop (Ghent). You had HD with film lenses, mini DV and then there was film. With film we wanted to go for cross processing or reversal. Our producer had no idea what we wanted to do. (laughs) I was a little worried as well, so I slept on it. We were looking for the color pallet of Wong Kar-Wai and Super 16 reversal gave the best results.

With a blow-up to 35 for projection?

We were looking for that big grain. De blown-up mini DV was not better, and 35 was too expensive. Our choice was quickly made and after a day of testing we decided: “Let’s film on 160 ASA.” (laughs)

I did make one mistake though. I used a polarizing filter in a couple of outdoor shots and that made the shine disappear. Leaves in the trees usually reflect too much light, and with a polafilter you can eliminate that effect. But that was the only thing I didn’t like. The sky was blue already, but it took away all dynamics, in the faces, the backgrounds and the leaves.

Let’s jump to The Broken Circle Breakdown (TBCB). When did you get involved with the project?

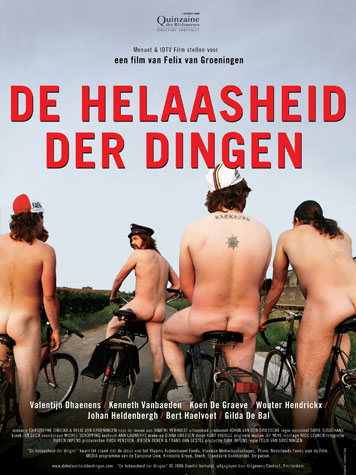

I remember that Felix told me after doing his movie De Helaasheid der Dingen: “I got it. I need to surround myself with people I trust and then everything will fall into place.” Mind you, he is a director who wants to have a say in everything, from the beginning to the poster, even to the wrap party… Everything. But that’s what makes him so unique as well. Throughout the years his trust in people did grow.

The first movie we made together was an amazing experience, because it was so exciting. The people involved were pretty crazy and everyone looked forward to participating in the project. There was, however, also some tension. It wasn’t the greatest collaboration and I remember being lost a few times as we didn’t always understand each other so well.

For example, we were shooting a night scene, but were behind on schedule and the sky was already turning blue. Felix couldn’t take it anymore. (laughs) I, on the other hand, absolutely loved it because the building became slightly detached from the sky, which was beautiful. I told Felix: “It doesn’t matter, we’ll shoot for half an hour and it’ll be amazing.” He ran away in anger to the median strip, and we stopped shooting. That was pretty intense. We also had arguments about issues we never argue about nowadays. At that time, I also wasn’t as experienced in convincing him about certain things as I am now. I didn’t know everything yet.

I got involved with TBCB early on in the process, because I think Felix appreciates my opinion. He doesn’t necessarily follow everything I say, but he certainly values my outlook. Therefore, he wanted me to be present at many rehearsals, which was also the case with De Helaasheid der Dingen. The read-throughs were filmed with a small video camera. Felix then watched all that footage and often rewrote the scripts based on it. That was his way of working. It was a luxurious situation, which is not always possible, but when it is, it is great.

Did you watch other movies together?

Blue Valentine (Derek Cianfrance) and the prison movie Walk the Line from Johnny Cash were very inspirational, especially on the level of podium performances.

Did you ever consider shooting on film for this movie?

De Helaasheid der Dingen was the first movie I shot with Red One. Felix really embraced that. We had a depth of field and a latitude of like 35 mm. It was also a pretty manageable camera and the image quality was incredible compared to what existed as HD-formats with adaptors and such.

We had a screening in Paris of De Helaaasheid and during the Q&A afterwards someone asked us on how many stocks we had shot. (laughs) That was a huge compliment, and it was because we had chosen to treat different periods with different grains on the Nucoda. I found that a very satisfying grading system. It has some kind of “re-grain” that you can set gradually. Felix likes to shoot a lot of material, and when he begins a scene there has to be space for improvisation. It was freeing for him to not have to worry about every inch of film. I remember some intense scenes where he simply let the camera roll to keep the actors in the right mood. He wanted to give them absolute freedom. That’s why we never considered shooting on film for TBCB.

Why did you choose the Alexa?

Because I like that camera slightly more, especially in the color saturation. Not necessarily on the level of definition, but more for its texture, skin tone and latitude. There isn’t a large difference with the Red Epic, but I appreciate the reliability and manageability of the Alexa, a true camera.

How did your prep and test phase go? You’d decided early on what you were going to shoot, but did you still do many tests?

Actually, I didn’t. I only tested a couple of things, in particular those scenes with the red light, because I was a bit worried about those. These were sex scenes and at a certain moment the light moves to red. I was especially curious about these.

Was the Codex ever an option?

We tried, but decided not to shoot on Codex. In fact, I’ve never been able to shoot on Codex yet, because it’s so expensive. I did the tests, but I found the difference too small and, to be completely honest, less beautiful. I thought the Codex was too sharp.

Which lenses did you use?

We finally went for Master Primes. You can shoot with maximum aperture without any issues, and with strong backlight the things are still solid. You also start from a very fine image in the grading, I think. If you do that with old Cooke lenses, you’ll have to double the effect. You’ll get many internal reflections and the image will become very unclear. We thought it had to stay fresh.

Meanwhile, however, I shot my last film (Trouw met mij) with Leica Summilux lenses. These are compact, very sensitive to light, with a nice flair and they are slightly softer compared to the Master Primes. They create a beautiful blur in the depths. Also nice is what they do with the shadows. These are a little grayer, sort of bleached, and that is interesting. If I have the option, I’ll definitely use them for my next movie.

But that option wasn’t available for TBCB?

No, it wasn’t.

Did you quickly decide on which gaffer you were going to work with?

My gaffer was Nicolas Lagae. He was not as experienced as a gaffer but I already knew him for a long time, and he knows how I like to work. I did know him before as lightning technician.

Even though he wasn’t very experienced, you decided to work with him?

Yes, because he does a perfect job. The good thing about him is that he’s got a great eye. I really appreciate his opinion and he often comes to tell me things as: ‘I don’t like that, is this necessary, shouldn’t that lamp be a little…’ and I appreciate it when he utters his opinion. I usually know what I want to do with the lighting, but the gaffer needs to be an added value, he needs to add something to it and have an opinion. A gaffer needs to be someone who is organized, yet at the same time he needs to be relaxed. Also, he shouldn’t take himself to seriously, because then it won’t work.

Of what did your light kit consist?

I really love Dinos. The idea was to not work with a large light kit, but with a couple serious light sources, to compensate. So we didn’t have trucks loaded with lights, but simply used two Dinos and a couple of smaller sources and reflectors in addition. Often we only worked with one lamp outside and its light was then reflected. I prefer working like that. If you need ten light sources in order to lighten a scene something is not right. I also find the combination of daylight and artificial light interesting, usually partly corrected and then I just play with it. When I light something up using a combination, I can perfectly key my 3200 Kelvin afterwards and make things red, if that is what I want. You can take it pretty far.

You often create an atmosphere of warm and cold light, inside as well as outside.

That was a deliberate choice and I’m less afraid to do such things now. For my last movie (Trouw met mij) I worked with many Led-sources that were already eight years old, but are not often rented out because they’re not color-correct. But I think that has its charms. You never have just one tint in the movie; there are however separated tints, which allows you to grab one part in the grading en pull the rest out of each other. I once did Code 37 with rotating stage lights. You can continuously adjust the complete color temperature and change it when and where you want. It’s a great tool with as benefit that you have many options in the grading. You have to follow your emotions in deciding the mood. Felix calls this emotional grading.

For the performances in the movie I also worked with filtered lights, usually blue backlight and warm key. For a scene in which Maybelle lays in the hospital, it was different. The diagnose was made, but she doesn’t know about it yet. Only her parents know what’s going on. And at that moment, I let the sunlight in. We placed the Dinos outside, on the 17th floor and the light burst inside. In the scene with the stars I just went with the coldness of the moment and the clinical environment.

To go back to your specific podium look. Did you choose a general approach for all of the performances?

No, we chose something different for each venue. The reason for that was the decor that was always different. The Roma, for example, had a red backdrop which I didn’t really like. Felix, however, did. In Ghent we had a venue called De Vieze Gasten, which was basically a black box. At such moments you should dare to shoot what you got, I think, and own it. I was never afraid to lighten things out sort of ‘in your face’. Straight forward, with a hard key in her eyes and then detached from the backlight but without wanting to pimp it or make it more beautiful. The harshness of that light, contrasted with her white dress, was quite beautiful. In another venue, Eldorado, the idea was to create the atmosphere of a church during Johan Heldenbergh’s speech. We did something theatrical, with candles and more low key, but that was cut out eventually.

Do you use other tools?

I always cary a Led Lenser pocket lamp on set. They give a strong beam, but you can easily make it diffuse with a Depron kegel. It’s an incredible mobile light source. I bought some for my last four movies as I needed many flashes from photo cameras and with a real flash you always lose the effect because of the shutter and the halved images. Reflected on a white board is always a great flash effect. I took them to Belgrade for the new film from Marinus Groothof and I had to leave them there as my gaffer completely loved them. I exchanged them for Rakija. I was stoked though! I recently saw some of these large LED-sources on a couple of fairs, they have the same output as a traditional 12K but they’re more compact. I’m sure we haven’t seen the end of it yet.

I shot Adem (Hans van Nuffelen) on film and then the first focusable LEDs just arrived on the market. Gaffer Mark Baller had bought some of these things and wanted to use them on set. I thought I’d give them a try, but the results were pretty disappointing. The combination of the existing neon lights in the hospitals gave a strange shift in color; something you can’t completely fix in the grading. Film is slightly more sensitive to that.

Did you work with storyboards and shot lists?

(Thinks) We did not make storyboards. Unfortunately, I can’t draw. But I did use many pictures. A lot of the preparations and rehearsals were filmed and I used stills from that footage.

So you get a lot of inspiration from rehearsals?

Yes, even though these are not lighted out. It’s purely about framing, distance and lenses, shot with a small video camera. Nevertheless, you can easily find out which perspectives work. We had quite a short list. Half of it was footage, stills and pictures from rehearsals. Such a list is never binding, though. You have to stay alert for ‘happy accidents’, things that are offered on the shooting day. These moments should be embraced.

Such things occur?

Yes, although for the largest part everything has been decided beforehand, we easily step away from those plans. I love shooting well prepared because with a good preparation you have the liberty to not do something, to do something else.

I think there was less improvisation in TBCB than in De Helaasheid, partly because we decided to work on a dolly. This is a traditional approach that makes it more difficult to improvise. De Helaasheid was more rock-‘n-roll on shoulder and then you have more flexibility.

What kind of grip did you use?

My key grip was Yves Crabbe, he rolled out a lot of meters, actually, and everything was on track. We had four days of Steadicam (Manu Alberts), very enlightening. I had figured out a choreography for the stage in the Roma where the camera continuously rotated around the actors, right beneath eye level (shadow and light). We eventually decided to combine this with steady shots from the venue, and in the hands of the editor it took a whole new direction. That is not an issue at all, as long as the scene works in the end.

Did you have any technical issues?

The bird, that was difficult. (laughs) We fixed it in such a Belgian way, but it was pretty funny. We had an animal handler with a raven, a bird that’s about half a meter large. When circling around the house, you can spot the bird, and once you know it, you’ll notice. They let it fly on a leash. We then threw a dead bird, a falcon, against the window. There weren’t many alternatives. Either you create one in 3D, which costs a lot of money, or you try putting something together on set, and that is what we did in the end.

How was the workflow? Did you use LUTs for viewing on set?

The workflow on set went quite well. I did not use LUTs though, only the standard 709 to view. Actually, I never really understood the whole LUT-thing. For my last movie I had twelve different LUTs in my camera, made in advance with Arri software, but after the second two I already had decided not to use them. Every time you change your reference, you tend to get lost in a way. You do need some kind of grip. The simple rec 709 look is definitely not what the final results will look like, but combined with logC, I know enough. Very simple.

Do you use a light meter?

No, I don’t measure light anymore. Sometimes I will measure during pre-lighting, or on recce, to measure how much light is available and how much light seeps in. Everything else I do without measuring.

Do you use filters?

No, I used to in the past, to make things softer, but I came back from that. You can easily do in post-production.

You have to be careful with ND-filters. Sometimes there were differences between them, for example, large differences in color, sometimes green, sometimes magenta. Luckily I immediately noticed this and we got a new set.

Did it contain a build-in control system? Did the image get verified?

In general, the rushes were verified. I received the dailies via Wetransfer, but those were the compressed files and you couldn’t see much on them. There was someone who made a quality report, but we did not have DIT on set.

Did you have enough shooting days?

We had 36 shooting days, which was enough. But I often shot extras with Felix during the weekends, rock-‘n-roll in a way, pure atmosphere, like Felix running after cows. You should see the rushes, and all these images were collected. It was really funny and we got plenty of use out of the images we shot. We had many images of birds, horses, nature, clouds, mills, etc. We left the tripod in the pick-up on Friday night, and during the weekends we would ride down the Kennedylane (canal zone in Ghent) to film, just the two of us, without any sound recording.

To what extent were you involved with the grading?

It just became a substancial part, laying down your look again. It can be completely ruined in the grading. It was great working with Peter Bernaers. At first, we were going work without a LUT, like I did in Brasserie Romantiek. But as soon as you don’t start from your film curve, you get this unnatural digital feeling. When you compress your image, and work with a LUT, you actually throw a lot of information away, but we preferred it that way. Though, I haven’t figured it out quite yet. The funny thing, I find, is that the human eye lays closer to the digital image, strangely enough. We distinguish many gradations, a lot of detail, but we’re actually conditioned by what we know through film. Take, for example, HDRx. I once tested that, but it didn’t work. The image loses its poetry.

Just like the discourse on latitude. As soon as there were eight to nine stops, I let it go. All these cameras, I don’t have to see them. An image in which you turn from the inside to the outside, with the same lighting outside and inside. Then it won’t work anymore, which is a strange contradiction to me.

Anyway, you should choose your palette as if you were a painter and direct in function of your story.

The Broken Circle Breakdown (2012)

Credits

Cast Veerle Baetens, Johan Heldenbergh, Nell Cattrysse, Geert Van Rampelberg, Nils de Caster, Robbie Cleiren, Bert Huysentruyt, Jan Bijvoet

Photography Ruben Impens

Editing Nico Leunen

Sound Jan Deca

Art director Kurt Rigolle

Costume Ann Lauwerys

Makeup Diana Dreesen

Music The Broken Circle Breakdown Band o.l.v. Bjorn Eriksson

Sound design Michel Schöpping

Technical specs

Running time film 100′

Release format ARRI Alexa

Other available formats DCP, HD Cam, Digital betacam, dvd

Aspect ratio 1:2.35 (scope)

Sound format 5.1

Colour Colour

Available in 2D

Arri Alexa

Master Primes

translated by Dylan Belgrado.