The enigma that is Nicolas Karakatsanis

A little while ago I had the honour to spend a few hours talking to one of Belgian’s finest cinematographers. Back home for a short time from an extended pre-production period on Disney’s Cruella, I met Nicolas Karakatsanis in his home in Brussels. We spoke about the Belgian film industry, the benefit of working on celluloid, his aversion to the use of references, his work on Le Fidèle, and his absence from the SBC roster. I started by asking him what he thought makes a well photographed film.

NK: “A film either works or it doesn’t – I honestly believe a good film survives without good cinematography. It needs to be filmed of course, but there are plenty of examples of great films that are shot in a rough way, but they work. At the same time, there are many films that are very cunning in the way they were shot, but they don’t touch a soul. In the end its about a balance between the different aspects of a film, a story that feels right, with emotional integrity. An example is the show Big Little Lies – I find it incredibly boring to watch. It works solely on editing, covering up their non-plot with effects and editing clutter – I just want to see actors act – it is as simple as that. Take a Harris Savides for example, he started quite bold and big, but the more he progressed the more he fell back on simplicity, keeping things small. It shows more character to keep your eyes on the project at hand, and base your approach on that – rather then aiming for bigger and more complex – just because you can.

Seeing the photography of a film as such an integrated aspect of the whole process, how do you relate to all the aspects of the process that are not under your control?

NK: I always keep an eye on the assembled team – and if I feel that the general elements are solid, its a matter of trusting that people came to the project for the right reasons – I am not going to micro manage things. People were hired to come do their thing – and I believe you need to let them do so. It can be very annoying when a production designer asks me about every single colour he/she is considering to use; I don’t go around asking people what they think of the lights I might use. In the end, the director is the final boss – if he/she is happy with something I am happy to find a way to make it work.”

A few years ago they celebrated the 20th anniversary of Titanic. Russel Carpenter hosted the ASC instagram around that time and came forward with a post in which he confessed how miserable he was during the making of Titanic, and most of the projects he did afterwards. Only in recent years, he said, he had found joy in his profession. How do you experience life on set – do you experience joy behind the camera?

NK: I like my job – I guess I set out from some sort of a naive sense of potential – knowing that a certain project is a good challenge. Of course this sense of challenge fades with the years as you get more experience. I have had the good fortune that, some commercials aside, I have not come across complete mismatches between a director and myself. On those few exceptional bad experiences I just see them as exactly that – I take those experiences to what is to come and learn from them. At the same time – for me its not paramount that the vibe on set is all fun loving times. If its hard work, or long days, so be it – the priority should be the end result. The most joy I find in seeing that final result and evaluating why it worked or not – seeing the pay off. A fun set is not always a sign of a good movie in the making, nor vice versa. A great example of this is The Revenant. The only marketing hook they had for that film was how hard it was to make – but besides that trivial fact the whole thing is totally forgettable.

How do you see living and working in Belgium?

NK: I love living here – its always great to return home. The last 12 years I have been very busy abroad, and it is important for me to be able to pull back from those other industries and come back to Brussels. Quality of life here is great too – seeing people that made the move to L.A. and how they need to shoot commercial after commercial to pay for their big villa and their kids’ expensive private education – it just doesn’t seem that appealing to me. Creatively Belgium is great. Whether you look at photography, painting, fashion, all sorts of creative disciplines, Belgium is quite a fertile ground. People tend to come at it from a pure angle; the chances that a lucrative carrier comes your way in the creative industries here are small – you have to be quite passionate and fearless, which are healthy mind sets I think.

What I do see as a slight weakness in Belgium is that we have a bit of a rock’n’roll reputation: we do a lot for relative small budgets. Which is great – but at the same time Belgium shouldn’t be a country in which industry rates are vague negotiable concepts – in Romania or Ukraine rates are negotiable; The UK, France, The Netherlands, Germany, rates are much more standardised and clear cut. Why is that not the case here? It would get rid of a lot of frustration if it were. Belgium can certainly shift gear a bit; the work-hard-play-hard attitude sometimes leans towards a builder site mentality; grips drinking litres of beer after wrap, and then driving home with a truck full of gear – getting bigger with the years. There should be more to the job. We miss a bit of focus, professionalism and unity. With the volume of work coming to Belgium there is also a slight rushed rank climbing practise in place. Young guys move to become heads (grip or light) cause there are not enough crews to cope with the demand – great! Good for them, but it does means they stop learning from their seniors and remain mediocre for the rest of their career.

Which cinematographers have inspired you in your work?

NK: None! I do’t find it particularly interesting to single out a cinematographers work. A film is good – not a DP’s work on it. There certainly are people who I think have done great work – but they just as much have done bad work. For me its always the full package, not one persons work on it. To go back to Harris Savides, he has done incredible work – but just as much quite a few bad things. Referencing and singling out stylistic elements of past work is really problematic in my opinion. I never watch references during pre-production. Mostly directors would ask me to watch scenes or films they find relevant. I can’t help but wonder though; are they hoping to copy these references, or do worse, cause clearly they can’t come up with good ideas themselves. Your screenplay has to be the base, it is as simple as that. Copying past work can only be an exercise – I don’t think Orson Welles was watching other films while preparing his films. What people tend to forget is that the films they watch as references will be used as a reference by thousands of other people as well – its much like the google algorithm; everybody ends up making the same movie. I see this everywhere; this film reality; lamp covers – yellow, window treatment – broken white, cigare color – everything needs to be backlit, colors desaturated, dim and dark lighting, its a pile of cliche’s because directors don’t stop referring to what they have seen already. It is far more interesting to explore the possibilities and not do what you know works.On Triple 9 I did not watch other police or heist films. My main source of inspiration was Robert Adams. I wanted to keep away from the cliche blue light that police films always seem to use. On the film I am preparing at the moment we had a show and tell a little while ago – I did not show anything. The costume and locations will dictate the look of the film – my base concept is simple: the film tells the tale of Cruella Deville and how she became what she is known as. Her world as she came up was one of london’s 70’s shabby punk culture. For that world I plan to use a super35 sensor, handheld. At the same time she has a nemesis who she looks up to and wants to replace; a fashion icon that lives in a glamorous grotesque world. So this world I saw – from day one – in a much more elegant 65mm format, with dolly, crane, or steady-cam. Then, as Cruella’s world starts to become that of her nemesis our visual approach gradually becomes more elegant and robust.

What else is part of your pre-production process?

NK: It very much depends on the director I work with. With Craig Gillespie we work from floor plans that he draws. So a lot of our setups are planned and plotted. But with Bas Devos the visuals really stem from what he has put together in the script. His projects usually have about a year of prep time between getting financially green lit to shooting – so its a long pondering and tinkering process of figuring out how to best execute the ideas he is after. On our last film together – Hell Hole – we shot a scene that played entirely in a crane move revolving around a house. Not that we thought about it for a year – but a lot of time was spend on finding the right location, and finding the right way to make it work in that location. We got very lucky with this bungalow like house, that had a little toilet just in the middle of the house. We put in a support structure there, from the foundation upward, that provided a platform on the roof that could support a 2 ton GF-16. Dries Leerschool – the key grip, had to consult proper engineers to make sure the whole structure was safe. He then used a laser and a bunch of marks to be able to manually replicate the swing at the different times of day we did them at. In the edit Bas found that the takes were consistent almost to the frame. It needed no help in post. That takes hard work, talent and incredible craftsmanship. For me cinema is a raw medium; you can’t look at it as too cerebral; only the broad strokes remain, details in cinema get lost. Unlike in a novel, cinema is not a medium you can layer with a myriad of details. No one will see them or care anyway – unfortunately. On the flip side, images are rich by themselves – with simple moves, music, composition, you can express what you are trying to say. Overloading with micro-ideas is so unnecessary. I sometimes see production designers pain themselves with endless tinkering about this dark blue or that dark something. I often end up saying I honestly don’t have an opinion about this.

What is your view on celluloid and how do you maintain such an organic look when shooting on digital formats?

NK: In digital you are a bit at the mercy of a colourist of course. The grade can take the image in all sorts of directions – which can be quite problematic. Film has less flexibility and thus requires more precise decision making on the day. So from a process perspective I much prefer celluloid. On Cruella we have been doing tests of both Alexa and 35mm. The results were graded by Tom Poole – who I worked with on I, Tonya. I must say, he really knows how to bring both media extremely close to one another. The one clear difference to my eye is film has more depth due to its grain structure – while digital is a bit sharper due to the lack of grain. In general I really just follow a gut feeling of what I find beautiful and what I don’t find beautiful.

Do you monitor on set with a specifically designed colour manipulation in place – do you use LUTs at all?

NK: I don’t. LUTs are meaningless to me. I have used 709 on all digital projects I did – save The Drop, where we used livegrade. It was a good experience, but Im not really used to exposing to the likes of a DIT on set. I expose for the log signal, and whatever LUT you are using – be it 709 or something you build yourself – is just an interpretation of this Log image.

What are your thoughts on lenses? I hear you are a Leica man.

NK: My taste in lenses is constantly evolving. I had a long period where I was into anamorphic lenses. At the moment I can’t see them anymore – I’m completely done with them. I remember when I started out – not having completed film school – I dropped out after 3 years at St.Lukas – I just learned by trying things out. Seeing films like Die Hard, or Leathal Weapon, I was very attracted to this full, proper look they had. So on a commercial at some point – something for a radiostation I believe- I managed to convince the producers to spend 4 times the price on an anamorphic lens package. Vantage was a fairly young company at the time, so we managed to get our hands on a German equipment package. The images really were amazing – I was completely sold. Unfortunately since then, vintage lenses and anamorphic lenses have become a bit like an instagram filter. The newer anamorphic lenses are huge, not particularly fast, and quite flat and dull in terms of their anamorphic characteristics – So I don’t see the point of them. The Primo’s are the only anamorphic lenses that I really liked. What the leica’s give me is a softness and humane texture, with a beautiful bokeh – that is why I like them. In the end your framing, and lighting is what your photography consists of – not just picking the most beat up old pieces of glass and then claiming that that is your look.

Last year you received an Ensor for your work on Le Fidèle. How did you approach that project?

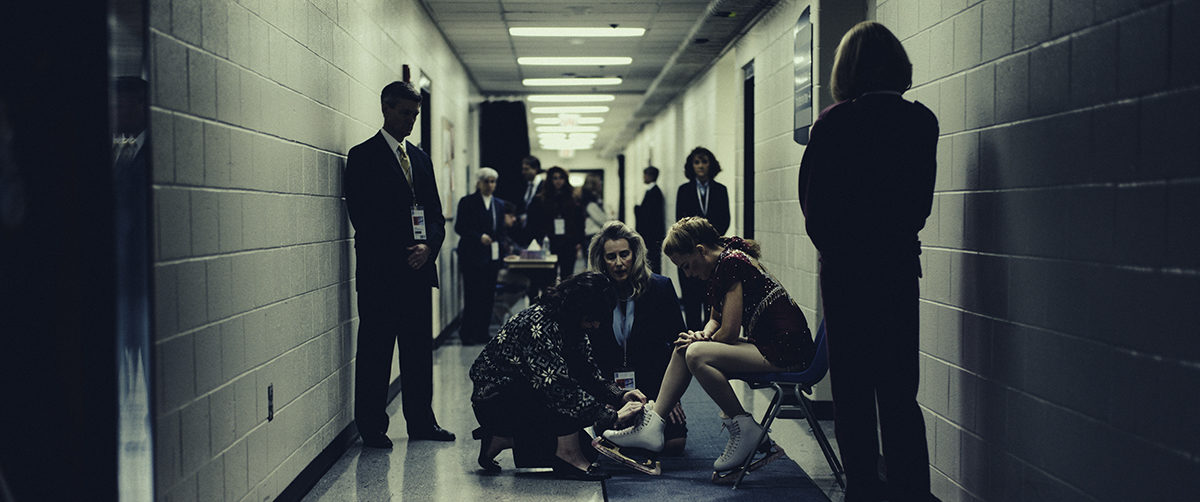

NK: My base concept for the film was to follow the evolution of Matthias’ character with the texture of the image and the way the camera behaves. We originally planned to do the final print on celluloid – which ended up not happening – but I wanted to keep that first part of the film digital, then go to 100ASA, and gradually, as the story gets darker and the two characters fall apart more and more, the operating gets rougher, the ASA rises up – things disintegrate. Seeing Matthias in his first frame and last frame – its kind of a different person. It was important to reflect that with the photography.

There are quite a few scenes in the film I would like to ask you to speak about. I noticed the daytime exteriors at the racetrack were too dialogue heavy to rely on available light – yet they look quite natural – how did you do that?

NK: It was a bit of a challenge – we had alternating sun and rain those days – and we knew the look for those early scenes had to be colourful, sunny, high-key. So everything had to come from our own lamps, rather then rely on available light. I wanted it to have a quite classical, refined character. Early on in my carrier I relied on available a lot. Partially because of budgetary reasons – it was also less common back in the day – and my knowledge of light has developed as well of course. I used book-lights a lot, negative fill, and quite a bit of backlight. Any direct we cut with big silks. Quite classical American light basically.

A scene that jumps out to me is the driving scene were Bibi roasts Gigi about who he is and what he does, while she races through some fields in her porch. Its a drama scene with action tropes inserted. How did you approach this?

NK: It was quite a difficult one that. That Porch is such a small car, its hard to rig any camera inside of it – especially with an anamorphic lens. We ended up rigging the Porch to an Audi RS6 – with the entire front part of the porch de-mounted. This gave us a sense of the road, and allowed us to hit quite realistic speeds; we moved at about 80-100km/h, which on the wider front angles felt really fast on those narrow roads. It was mostly challenging to keep light continuous – at those speeds I could not really have any flags in play. I look at the final scene and do see how the light jumps quite a bit at times. But its a great scene, from conception in the written it already was quite an unusual and interesting scene.

The scene where Gigi and his gang have a dinner party and end up singing Gigi Amoroso is quite a strong set piece. I hear it was shot the day after Mathias’ mother passed away. How did that scene come about? How did you keep a good overview over the many angles required in that scene.

NK: Indeed, it was quite unfortunate. We knew it might happen, and production was prepared for it. When the day came we had the option to stand down for a while to let Mathias grieve. In the end he decided he rather kept going – so thats what we did. It was shot day for night, so I had to tent the windows in that bar (the careful eye might see a few things that give it away actually) and we used back projection inside the tent with night exterior plates we shot in advance. The scene was shot over 2 days, with an occasional second camera added. Michael and the actors had a day of rehearsing in advance, as there was quite a bit of angles and blocking to be figured out. I tend to just keep things in my head on chunky scenes like that – after analysing the angles from the script I stick to my gut feeling for coverage.

The most spectacular action scene in the film must be that highway robbery on the money transport. How much of that sequence was helped with GCI?

NK: there was only one CG element in that sequence; the falling container. So initially we had a container on the bridge and on the highway – the falling container was added and one of the two real containers was painted out on each end of the fall. The build up was all for real – Russian arm shots with the car; quite standard. Then we cut into the car, with a camera on a flight head mini, on a slider, with the back door taken off for the camera to slide out. This shot looks over Gigi’s shoulder onto the road. After the car comes to a halt; a grip pushed the flight head across the slider and out of the door, which gave us the wipe to cut to the steady-cam shot that continued the shot.

How do you see the future? The Disney film you are prepping now is quite a different direction from what you have done so far; do you hope to develop more in this direction? Is this the beginning of a new phase?

NK: I am doing Cruella because of Craig – a director I know and have come to trust. Its also not a lion king or little mermaid – its an origin story, with quite a lot of creative freedom for us. In the end its a challenge, that I am very happy to take on. I wouldn’t be interested in doing a Marvel film – but bigger projects with a certain authorship from a strong director I would certainly be up for.

I like the variety in doing small independent films as well as bigger budget commercial films. I must say though – whether you film a smaller film with a small form factor – like a regular house – or a big Disney film with castles and big scale sets – the concept stays the same, you still need to pump nice soft light through the windows; whether that is one small window, or 20 massive windows, its more of the same; you need to get bigger and more lights. Just a matter of allowing yourself to think bigger – and order the tools needed to execute these bigger ideas. I do have to look more for my personal connection to bigger projects. I need to know I can do something with the script that is genuinely interesting. It took me 3-4 weeks to get motivated to just read I,Tonya. At first I was certain that I was not going to do an ice skate film. In the end once I read it I knew I wanted to do it – but it took a bit of time for the idea to grow on me. One thing I know for sure, I want to keep away from doing the same film over and over.

To wrap it up I think we should address the elephant in the room. How come you are not an SBC member? What are your thoughts on SBC as an organisation?

NK: I have objections to two main aspects of the SBC as an organisation: its members are selected on very loose and vague criteria, and they are asked to contribute a negligible amount of money each year to support the organisation.I don’t believe you can build up a community without proper funds. For SBC to have value, its members should value it accordingly. With the tiny membership fee they collect nothing substantial can be done. It takes full time staff and members that care deeply about the organisation. Sometimes it feels more like people are in it for the status they think to get from those 3 letters behind their name on a films credits. There are too many things that should have been done a long time ago. I think of sharing access to new technology, organising tests, facilitating access to pre-release films.

Besides that, the meaning of being an SBC member is a bit lost – given the ease with which people are accepted as new members. It should be a recognition of your achievements, a responds to a remarkable body of work – rather than an obvious result of working on sets. This combined with a high membership fee would actually bring real value and meaning to the organisation. At the moment, in my opinion, there is very little meaning or significance to being a member of SBC.

Gaffer Tim Janssens was so kind to offer more details of how he lit the exterior dialogue scenes at the race track.

TJ: We shot that first scene were Gigi and Bibi meet at the boxes of the Zolder racing track. The idea was that it would have a certain Monte Carlo look to it. To balance the exterior daylight underneath those white tents we rigged them with 40 double tube TL fixtures. We used 2 HMI 18K’s for backlight – both full spot with 1/2 CTS. To fill things in we had an M90 around which we build a booklight. The scene with Gigi and Bibi’s dad we shot with a similar light package. I used silks over head, and made the other sources softer with 8×8 and 12×12 grid cloth. Throughout the whole film we wanted to have a gradual decent from a high-key, saturated, sunny look (mostly 18k’s) to a dark and dirty look (dirty fluorescent tubes) I was quite happy with the way this gradation ended up working in the final edit.

written by Seppe Van Grieken SBC