Kommer Kleijn, a digital pioneer…

Kommer Kleijn is one of those rare people: a true genius who has made major contributions to progress in our profession. Variously a Director of Photography, a keen stereographer, a teacher at three different film schools, a specialist in VFX, as well as in motion control and animation, the co-founder of several capturing processes, a scholar in the field of audiovisual perception, passionate defender of higher frame rates, a digital pioneer who also works on new loudspeakers. He is an active member of several committees and professional bodies such as the SBC, IMAGO, UP3D, EDCF, SMPTE and the AES, and was honoured with the Lumière Award for best European stereography in 2017 by the AIS, UP3D and “ Stereopsia” for his dedication to stereoscopic photography over the past two decades, as well as ‘best 3D feature’ for Above Us All by Eugenie Jansen at the 3D Image festival of Lodz in 2014. IMAGO paid tribute to celebrate this wonderful man by giving him honorary membership this March.

The Honorary Member Award handed over by IMAGO President Paul-René Roestad

So many hats for one man… Is your brain exceptional or have you just been working like a madman in order to accomplish so many things?

KK: Your question is very interesting, as in fact there are elements of both. I have indeed been allotted a slightly unusual brain and I have been working a lot as well. In fact, both are the result of a condition which was unfortunately not diagnosed until very late in my life. After a major breakdown, doctors told me in 2012 that I had autism. This is a generic term, which defines a range of anomalies almost as varied as the number of people afflicted, and in my case was diagnosed as Asperger’s syndrome. This defines a form of autism that has a substantial impact on the course of one’s life, but with a conscious brain that works normally and without speech impediment. This form of autism is all about anomalies in the unconscious information processing functions of the brain. Fortunately, as a consolation prize I had the gift of some unusual intellectual abilities that have allowed me to achieve what you mention.

As for the second part of your question, the word autism literally means one who becomes introverted. Suffering from this handicap, I have been struggling to understand the social world I live in and to establish valuable social connections, and I have over-compensated for this through my work. I was often socially rejected and I figured that if I was very good and dedicated to my work, then my peers would hopefully overlook my social deficiencies . The workaholism probably also helped to cope with the solitude caused by the disability.

In Munich testing a D20 prototype for ARRI (pre-Alexa) with a 3D lens, july 2007

With a brain like yours, you could have achieved anything: designing spacecrafts or medical research. How did you end up working in film?

KK: I believe it was a combination of circumstances. It may not have been the smartest thing as choosing a movie making career is not recommended for anyone with a condition like mine. But back then I didn’t know. This is what then caused my current illness, a condition far more problematic than my cerebral difference. By which I mean my current inability to work. I found it very difficult when I was told I wasn’t fit to work on a film set any more. I liked a lot what I did.

So how did you end up working in cinema?

KK: Cinema being so deeply attractive, I did not take much convincing. (Laughs). In fact I was raised in a family of musicians: my mother and my sisters are all professional musicians and my dad, although an engineer professionally, was also a passionate amateur violinist. Music, and the art of performing to entertain, was a core component of our family. Due to my handicap being undiagnosed, I was at odds with my parents which created much tension. Furthermore they were more advanced than me musically, and ultimately we had diverging musical tastes. I liked pop and rock and wanted to play the drums, while my parents played classical music and didn’t want a drumkit in the house. So I developed an interest in electronics and photography, a medium as technical as it was artistic. I spent long hours in the dark room, and I also liked fixing electronics. Thinking about it now, I was actually following a path that combined those of both of my parents: the artist and the engineer.

My first encounter with film making occurred when Dutch TV came filming at the house for a documentary. My dad performed in a string quartet and they came to record one of their rehearsals on a Coutant 16mm camera. So I fell for this wonderful tool which was able to make not just one, but many photographs in fast succession!

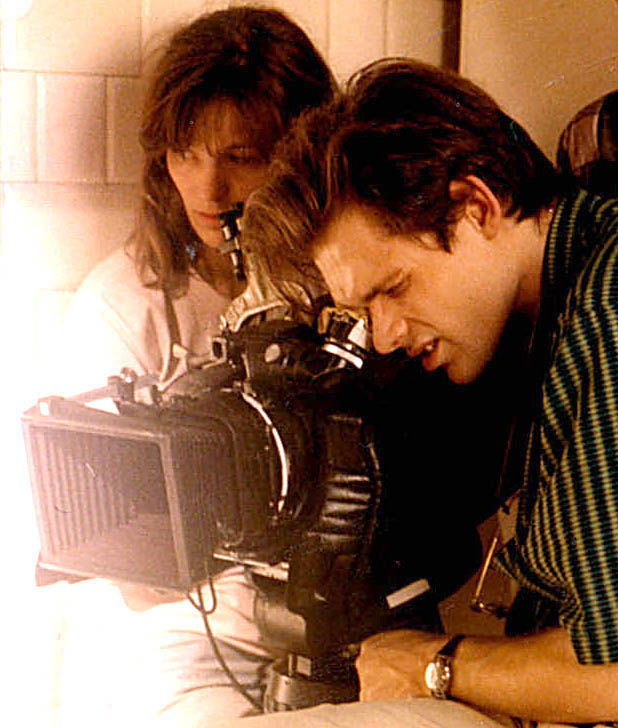

On set of “Het Ongeluk”, 1985, with Ella van den Hove SBC on focus. Dir: Jacco Groen

You are Dutch I believe, so how did you end up at Insas?

KK: As I was handy with electronics I initially went to an engineering school, the one where my father had studied. There I approached final year students to enquire about potential graduate work positions, and I have to say I was not thrilled at the prospect of fiddling with electronics in a lab all day (Laughs). My mother had a friend whose husband worked as a DOP on TV movies in France. She asked him if I could come over and spend some time with him. The instant I walked on a film set, I was hooked. I passed my initial exams to enrol at the National Dutch Film School, but I was so eager that I ended up failing. Luckily, these tests were held before the summer which allowed me to apply for other schools in the neighbouring countries. Belgium was a true haven for film schools. My sister studied music at the conservatory in Brussels and her teacher spoke highly about Insas. I nevertheless applied to both Ritcs and Insas. Ritcs advised me against pursuing their cinematography course in favour of directing because according to them, I was too intelligent! When my application for Insas came through, I chose to go there because I liked the movies shot by Ghislain Cloquet.

Your teachers were Charlie Van Damme and Ghislain Cloquet. How did it feel to learn from such iconic giants of cinema?

KK: I was very lucky to have them as mentors. We were not taught by Ghislain for the entire first year as he was working with Polanski on Tess, for which he got an Oscar. But as soon as he got back, he more than compensated for it. He walked into the classroom, opened his on-set bag and poured its contents on the table and magic happened. He also brought along his own personal 35mm print of the movie to screen for us. Charlie was perhaps not as eloquent, but shortly after graduating, I worked with him as a second assistant camera on Benvenuta by André Delvaux. I learnt so much from him. He is a wonderfully gifted man.

On set of “Le Huitième Continent”, a 3D interactive ride film for Futuroscope by Alterface

After some time, you specialised in ground breaking technologies : digital, compositing, 3D and more. How did this come about?

KK: Well, I see two ways to look at this: on one hand, the way I experienced it at the time and on the other, looking back at it retrospectively after my diagnosis. I was quite passionate about this profession. I was fascinated with using the camera as a tool to convey story and emotions, so aspiring to be a DOP on feature films came naturally to me. At the beginning of my career there were not many issues. During school I got many offers, the student directors liked to work with me. Similarly after graduating, doing shorts, I had an exemplary career as a camera assistant too. Offers to be a DOP on feature films however, were harder to come by. People were happy for me to be a technician or DOP on short films, but as projects became more substantial, they were looking for something more. As I was stubborn and unaware of my handicap, it took me a long time to realise that I wouldn’t be a DOP on feature films. After a number of years I came to terms with it but without understanding the reason why. I had invested much of my energy attempting to achieve this but on the side I have always made a living working as a technician. And people noticed I was doing well when there were unusual techniques at play. Although this was not my deliberate choice, I was nevertheless amused by that and I wound up doing more and more of that work. At first shooting in black and white, then VFX became involved: blue key and other kinds of composit photography, motion control etc. Then came the digital cinema techniques. I shot a lot of stop motion too and then stereoscopic 3D

On set of a Renault Twingo commercial made in clay animation, 35mm with animation director Guionne Leroy on the left

Were you never the DOP on feature films, even 3D movies?

KK: I have done long form 3D music and dance captures, some distributed in cinema theatres, but I have only been at the chiefs table on one fiction feature film, as a stereographer on Above Us All, directed by Eugénie Jansen, with Adri Schrover NSC as DOP. I was very happy to have made this movie as it corresponded with my vision of 3D film-making and the way I believe a 3D film crew should work together.

How do you explain that you never had the opportunity to be the DOP that you wished to be? Was your handicap the root of the problem?

KK: Yes, I think it was. Even though on one hand my autism doesn’t affect my creativity, on the other hand it causes a deficit in social communication skills, especially in non-verbal communication. Contrary to popular belief, my autism doesn’t produce empathy issues, but I do have difficulty reading the muscular clues taken for granted by others as a tool to read facial expressions and body language. My brain simply lacks the functionality of automatically decoding these. Subsequently my conscious self was trained to attempt to interpret it anyway, but that process is almost ‘manual’. The result is that not only my conscious brain is working overtime to compensate, which is exhausting, but also it is interpreting only 15%-30% of the clues! The main task of a DOP on a feature is to understand and feel what the director wants to say. On the short films, directors were concerned with the DOP exposing the film correctly. At that time I was valued by my peers because I was meticulous and technically able. However, on a feature film the main concern for the director is to be well understood.

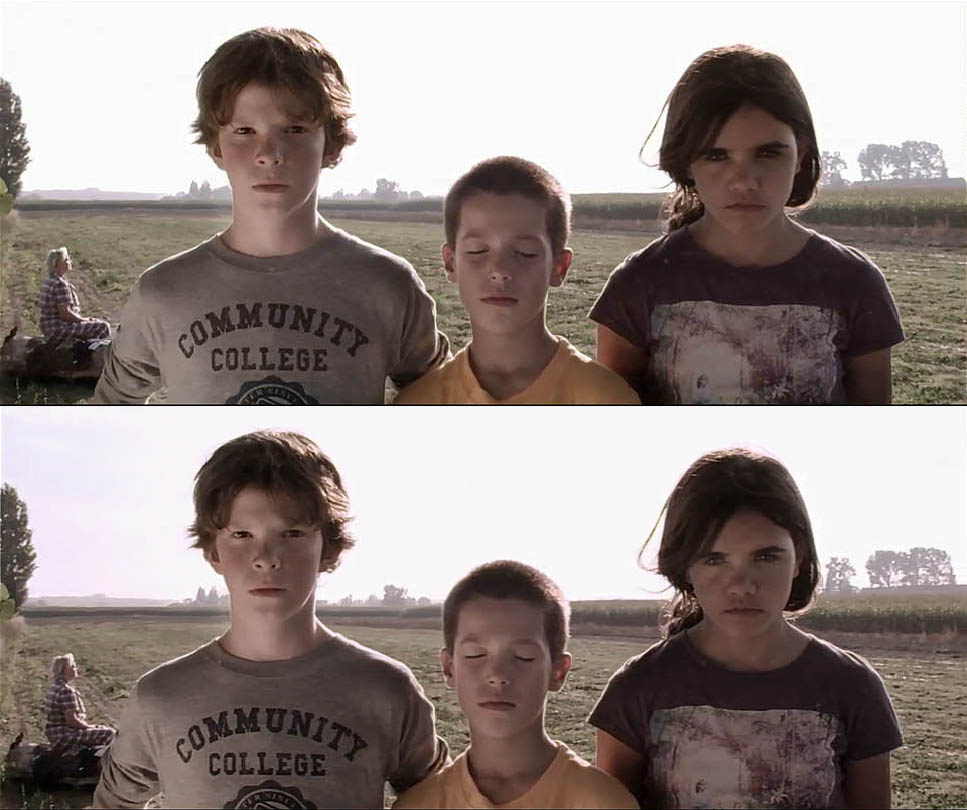

Above Us All. Dir: Eugenie Jansen, DoP Adri Schrover, NSC

Earlier, you spoke about “Above Us All” and how it corresponded with your vision of 3D film-making and the way you believe a 3D film crew should work together. What did you mean by that?

KK: For me, 3D film making, as with any substantial technological progress, only makes sense if it becomes part of the narrative. It is no wonder patrons become bored with 3D movies when in fact most 3D movies are just 2D movies shot with a 3D camera. For starters, 3D viewing is 2 Euro more and then has to be watched through tinted goggles that make everything dark. So if all we are offering in return is an occasional perceptual illusion gimmick, no wonder the customers lose interest. Above Us All, on the other hand, is a true 3D movie in that it offers a new film language that uses the 3D. The 3D is an integral part of the storytelling. In fact, there is no 2D version of this movie. Quite natural because if a movie works equally well in both 2D and 3D then that somehow gives away the 3D was not used in the narrative. When journalists told the director that it was very unusual to refuse 2D screenings of her movie, I suggested she tell them that she also refuses to screen her movie in black and white or without sound!

On set we blocked each scene the three of us together; the director, the DOP and myself. For me, a stereographer is not just a person who presses the buttons on the 3D rig, his role is to be in charge of the framing of the third dimension, in other words, the depth operator. But, as we all know, camera operating is not limited to just pointing the camera. An operator also has the storyboard in mind and will make suggestions for the set dressing, blocking etc… To be a stereographer on a ‘true’ 3D movie is to contribute much like a camera operator would, to all these components, which is what we achieved on Above Us All. We constructively collaborated harmoniously, inspiring each other.

Above Us All. Dir: Eugenie Jansen, DoP Adri Schrover, NSC

If I am not mistaken, this is not the only technical innovation of this project?

KK: True. It may be hard to believe this is a coincidence, but this picture is to my knowledge also the first movie truly shot and screened at a higher frame rate, and a shortened exposure-time per frame. Again by ‘truly’ I mean that the higher frame rate is actually used for the storytelling. Above Us All is not only 3D, but also constantly in motion. The movie opens with a still shot and then after a few seconds the camera starts a pan to the right and never stops. The scenes all appear as single continuous shots where the camera pans continuously like the hand of a clock, covering a full circle in each setting, sometimes even two. So it is in some ways also a 360° movie. There are cuts, but we go from one panning camera to another. As all this is unusual, the producer asked us to do three days of tests, shooting three complete scenes. So we do that, and when we screen it, catastrophe strikes: the picture appears blurry and it judders! There then is a discussion and I raise my hand from the back of the room and I say that this probably shouldn’t concern me since I have been hired as Mr. 3D, but that in other circles I am also known as Mr. Frame-rate, and that I think the problem can be solved by shooting 50 or 60 frames-per-second. The reply is that this will cause slow-motion. I say that we would also need to screen at that speed. The producer then says that this is impossible because cinema theatres do not project at 50 or 60fps and then I said that they actually can because people including myself have fought for that for about a decade and actually got that into the International DCP standards. So we conduct more tests, now at 60, and amazingly the images are sharp and there is no more judder. In the end, we have shot the entire project at 50fps and it was also always screened at that speed, everywhere. And same as for the 3D, there is no 25 or 24 version of this movie as that would be unwatchable. So the higher frame rate actually has been used in storytelling! Without it, the project couldn’t have been made in the way the director had imagined it. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first movie to achieve this. I think it is also the first movie exposed with a shorter exposure time per frame, 1/100th of a second. This was needed to retain image sharpness spite the continuous camera movement. There have previously been other movies shot and screened at higher frame rates, such as Peter Jackson’s ‘The Hobbit’, but they did not fully exploit the potential of the change in frame rate. Note these movies are not edited much differently and “24” versions also do exist, so they seem closer to a ‘normal speed movie’ that was shot with a high-speed camera. A bit similar to the 2D movies shot with a 3D camera. Shooting at high speed without exploiting the new storytelling possibilities that it enables has not much interest for the viewers. It can actually even be counter productive because twenty four frames per second also creates anomalies that people ended up liking, as they connect these with watching a movie in the cinema. This is what we call “Love of Artefacts”. Then, if you make a change to the emotional feel of cinema by removing these artefacts, but you fail to give something strong and emotional in return, then the viewer will again be disappointed.

On set of Above Us All by Eugénie Jansen

This brings us back to another of your interests, cinema projection. Can you tell us a bit more about this?

KK: Actually, it is not projection itself that I am interested in per se, it is again about the way cinema can convey stories and emotions to the viewers. I think a DoP must also consider how the images are going to be shown and received. Thus projection has always been of huge interest to me, even including sound. For my graduate documentary at Insas I choose to film the projectionists in my local cinema theatre because I noticed that they shared the same passion for this wonderful medium. I have also worked as a projectionist in cinemas myself. When the new technologies came I was among the first to shoot digital, and I was keen to follow the evolution towards electronic projection as well, like being in the booth the night the first ever digital projection happened at Kinepolis as well as building a small experimental electronic theatre as an annex to my house. For me, cinema is a medium designed to transmit story and emotions and therefore altering the projection system, if done badly, could destroy the whole thing, so that needed to be followed closely. I also took an interest in everything that could enhance the medium; IMAX, Showscan etc…the problem with analogue film stock is that these upgrades come at a significant cost and have consequences for the shoot (heavy loads of film stock, big noisy cameras etc.), so when we shifted to digital, I saw a huge potential there, as these constraints eventually now could disappear.

Above Us All by Eugénie Jansen

Earlier you mentioned the downsides of 24fps that viewers have become accustomed to. Can you list those?

KK: The major disadvantage of 24 is that the picture becomes “blurry”, low definition in fact, as soon as there is movement. With even the slightest movement this is enough to make a 4K camera virtually useless. The only way to make it sharper without creating strobe effects is to shoot and screen at a higher frame rate.

Read more on higher frame rates with Kommer Kleijn in Part II of this interview.

More about Kommer Kleijn can be found on http://www.kommer.com