The advantages of being a woman cinematographer

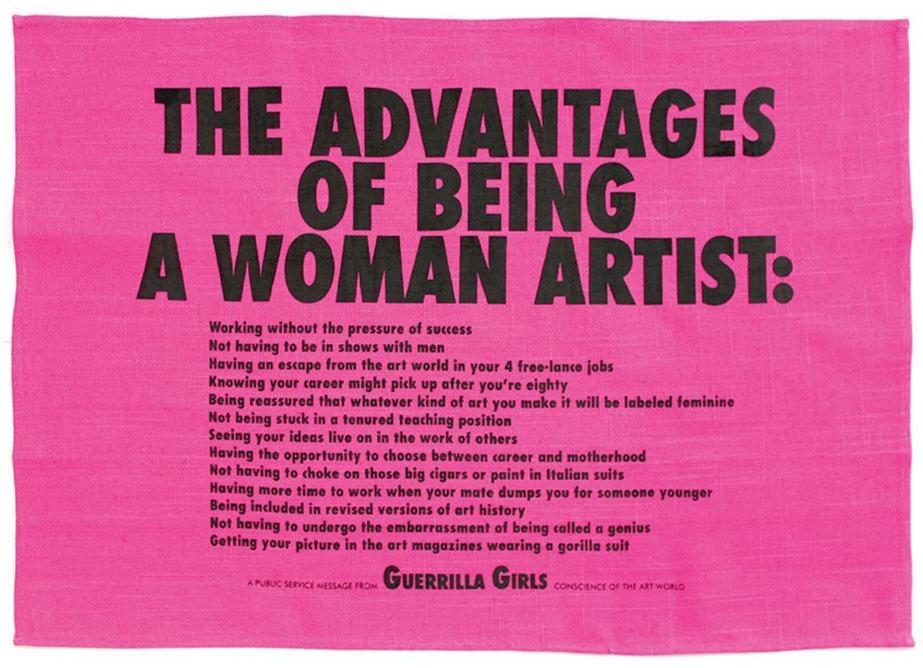

When I left home to study cinematography at the Insas film school, my mother brought me a gift from Great Britain: a fuchsia pink t-shirt entitled “the advantages of being a woman artist”, created by a group of feminist artists called the Gorilla Girls. I wore it proudly, first at school, then on set, telling myself that it was for fun and somewhat a bit committed, so it was a good thing to do. In fact, it especially allowed people to squint at my chest while pretending to read the text written in small print, just at the height of my bra. The fact remains that I did not understand until years later when I started working while becoming a mom, the “advantages” of being a woman and an artist. Noticing the growing number of female directors of photography joining the Belgian Society of Cinematographers, I wanted to meet them to see who they were, what their backgrounds were, if they had faced the same problems I did or others, and what their thoughts were on the label of being a female director of photography.

However, upon proposing to write this article to the SBC and then to the artists concerned, I immediately self-censored. In fact, in my introductory email, I ingenuously specified that I wanted to write about them without writing an “overly” feminist article; as if feminism was a taboo. As a reminder, for people who, like me, tend to give a negative connotation to the word, feminism, it is quite simply striving for equality between men and women. However, for the subject at hand, namely female cinematographers and members of the SBC, the observation is unequivocal: we can still progress. I say “we” because, contrary to what one might think, the inequality between men and women is not always the result of a 100% male machismo, but is also due to women themselves, who like me, self-censor, do not dare to assert themselves or simply find it normal that there are differences between men and women.

When I met these women, at the start I was struck by the fact that the oldest female members of the SBC were the ones most committed to the fight for equality, unlike the new members who often started the discussion by saying: ” for me, there is no real difference between my male colleagues and myself “. But after sharing some of their experiences on set, or for example a clash with the production about salary, they started realizing that in fact, they all had faced these problems, and that, no, it was not entirely normal. This difference in attitude is no doubt explained by the fact that in the early 1980s, it was very easy to become a camera assistant for a woman (or even easier than for a man), because they were recognized for their qualities favorable to that position: “being organized”, “rigorous”, “meticulous”. On the other hand, when it came down to moving up to become an operator or DOP, production managers worried about women’s ability to “be able to manage a predominantly male team”. Some operators did not hesitate to state openly: “being a cinematographer, this is not a job for a woman”. Of course, at the time, the first female cinematographers began to be recognized, like Agnès Godard in France, however, their success was still exceptional enough to be remarkable. In general, it was more common to offer women a teaching position than to have them collaborate on a film, especially when they started to have children.

Today, many things have evolved: cinematographers are not only better accepted by their peers as by the productions, but also win prestigious awards, such as Virginie Surdej who was awarded the 2018 Magritte for best cinematography for Insyriated by Philippe Van Leeuw, or Juliette Van Dormael who won the “best cinematographer’s debut” award at Camerimage, in 2016, for Mon Ange by Harry Cleven. And yes it is true that there is momentum for women in cinema at the moment. The 69th Berlin Festival committed in 2019, to promote parity in the cinema industry, by programming 50 percent films made by women or by having female jury members.

However, much remains to be done. Certainly, there are more female directors of photography, but in reality, there are many more cinematographers working today than twenty years ago and thus the ratio of men to women in this position remains more or less the same. However, there are often the same number or even more female students than male film school graduates. So what happens to them upon leaving school and looking for a job in the film industry. Many become camera assistants, some electricians, a few grips, and many of them teach and / or hold academic positions. For example, the remarkable gender parity in the education committee of Imago while women represent only 10 or 12% of the Imago members. It is true that the same is true for young cinematographers who are getting started. The relative ease to shoot made possible by the advent of digital technology, the multiplicity of film schools allow more and more people to embark on a career as a DP, while the film industry can not accommodate everyone to have opportunities in this position. Except that, for a woman, it is much more difficult to make a career as a DP than for a man. Proof of this is the eight women interviewed for the writing of this article out of the eighty-one members of the SBC.

An equally alarming observation: women cinematographers, with equal skills and levels of experience, are, for the most part, paid less than men. Unfortunately, there are no Belgian studies on the subject, but, according to a French CNC study released in March 2019, they would be paid 18.4% less than their male counterparts. This is partly explained by the fact that they are not offered the same films. In fact, except in exceptional cases, large budget films (over eight million euros) are offered almost exclusively to men. Of course, one can wonder if this glass ceiling is really attributable to their gender or consecutive to the skills and choices of each. However, when a production manager asks a female DP: “Are you able to manage a set of this magnitude?” We are entitled to question the double meaning of the question. Just as we can be worried when, during the casting of cinematographers, the production offers a higher salary to a male colleague.

So what to do? Impose quotas, in film schools, on set, and in festivals? The idea of quota is a good one because it allows establishing a legal framework, to impose a change of behavior in order to initiate a change of mentality. However, for most of the women I interviewed, quotas are often tricky. They themselves do not always choose their team according to gender, but by affinities and skills. Unless when they work on films having a female subject or on films where the team, starting with the director, is mainly female. Cinema is still predominantly a male art form depicting women from a macho point of view. Legacy of classical painting, the women on screen must be beautiful, desirable, sublimated by light. So the more the actresses age, the more the lighting must make up for their blemishes. Conversely, female cinematographers are chosen because they offer “a feminine look”, “an organic softness”, “a certain sensitivity”. In this sense positive discrimination is good, but should it be limited to a feminist cinema? Can they not, if they wish, shoot large budget commercial films? And if we look at the opposite problem: why would women need to change the way we look at women? On the contrary, don’t we need more feminist cinematographers, of whatever sex, if we want to change mentalities in-depth?

Another aspect of the problem, even if this concerns only a part of the female cinematographers, of course, lies in parenthood. It is much more accepted by society in general and by the film industry in particular, that a man travels far from his family to shoot, while, for a woman, one still too often has to choose between career and maternity. It is of course not a question of saying that the male cinematographers hardly care about their children, but it is clear that few of their female counterparts have the possibility, thanks to their partner or their entourage, to leave behind their children for long periods several times a year. The problem is obviously not limited to the film industry, but societal. For things to change, there must be real equity in the couple, starting with parental leave – which is far from the case (fifteen weeks of maternity leave for women against ten days of paternity leave for men).

But it’s also about changing the way we make films. Filmmaking as an industry, competition between cinematographers, economic constraints pushes DP’s to shoot back to back to gain experience and comfortable salaries. Some female cinematographers have chosen a different type of cinema, a little on the fringes of the film industry. They make films with less budget, which require a lot of personal investment, but which also allows them to enrich themselves professionally and humanely. Even if it means having less visibility than men, for them, it is necessary to take breaks between each film to be able to assimilate what they have experienced and better start on the next project, but also to find a fair balance between private life and profession-passion, without giving up their career … As I said above the subject is controversial and sensitive and it should be devoted to a more in-depth study, but women in cinema are on the rise these days, and our Belgian cinematographers are no exception, so let’s take this opportunity to find a fairer balance.

written by Leslie Charreau

cover photo by Lou Berghmans