The making of kursk

In 2017 “Festen” Director Thomas Vinterberg, one of the founders of the Danish Dogme movement, embarked on filming: “Kursk”. The film is based on the true story of Russian marines who drowned aboard their submarine in the Barents sea when help didn’t arrive on time after an explosion. The result is both a big adventure movie full of action scenes and a CGI submarine, as well as a classic Vinterberg drama. This co-production was mainly shot in Belgium and created around 2,000 workdays for technicians and actors.

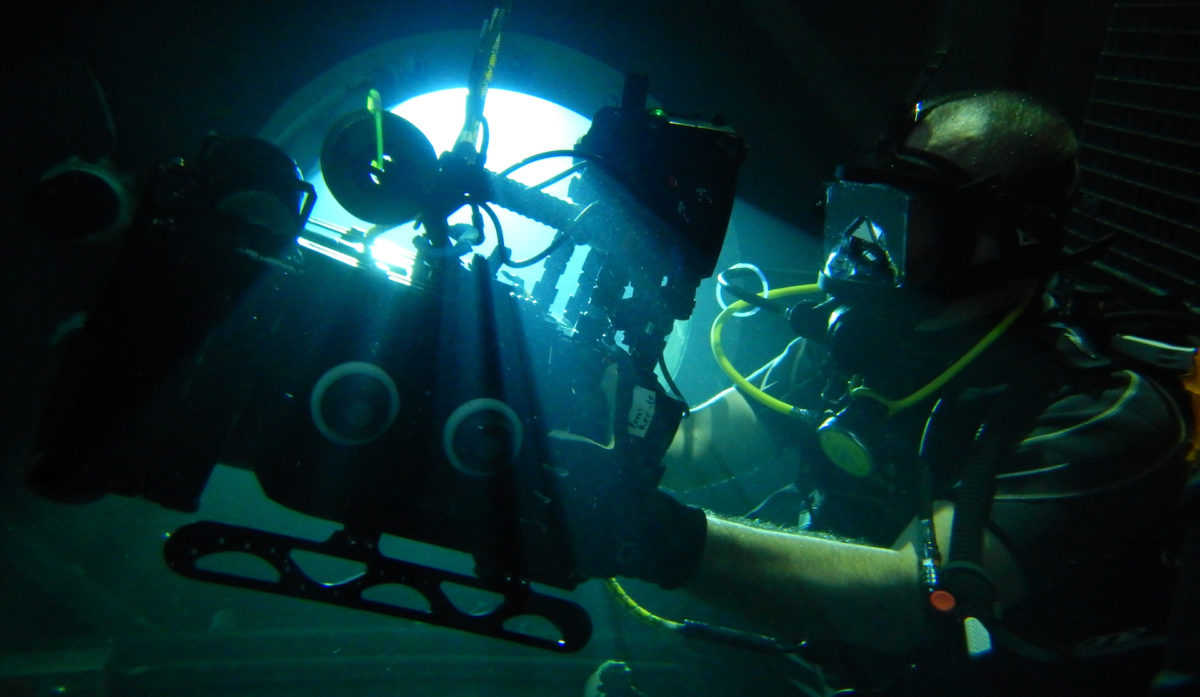

Under the supervision of Oscar winning DOP Anthony Dod Mantle (ADM), three SBC members worked on this production. Patrick Otten was the second unit DOP & Director / B-cam operator, Wim Michiels was responsible for the underwater shots, and Jo Vermaercke was appointed as steadicam operator / second unit dp-operator. SBC & mediarte spoke with them about their work on such a large scale set, the importance of internal communication, the complex technical challenges, and the feeling of being part of a well-oiled team.

It’s pretty unusual for 3 SBC-members to be working on the same international top-level production. How did Director Thomas Vinterberg eventually end up with you?

Wim Michiels: “We were contacted separately. The ball started rolling because of Laurent Hanon (Belga Film). All three of us went for an interview in the same hotel, albeit at different times (laughs).”

Patrick Otten: “Like my colleagues, I went for an interview with Anthony Dod Mantle through Laurent. I suppose it was after watching my showreel, IMDB, etc. During the interview it became clear there were some mutual connections with colleagues but also with technicians including Lester Dunton, who had built special camera set-ups for the film RUSH (2013, Formula 1, a movie about James Hunt & Niki Lauda, earlier work of ADM). I think the fact that I had worked with Lester previously and knew him well, as well as my love for lenses opened the door for “Kursk”. Originally I was asked to be solo second unit DOP for about 20 days. Quickly afterwards, during the preparations, I was asked if I wanted to take care of the B-camera alongside Anthony, and suddenly I was looking at 85 production days. This story had another twist when it appeared that I got along well with Philippe Desiront, the Canadian VFX supervisor on this movie. Since the scenes were pretty complex and technical with underwater shots, explosions, and green-key work, I was asked to be the second unit director from the CGI standpoint together with Philippe. It seemed to be the most obvious choice for the production given our joint technical background.”

Wim Michiels: “In the end, I filmed about 25 days underwater, which is significant. For my first interview with DOP ADM I had my showreel with me, primarily underwater shots, but ADM actually didn’t look at them. The conversations covered a hundred and one things from lenses to underwater shots to diving. It was more of a personal conversation. Afterwards Vinterberg joined the conversation and my role on the set was decided upon pretty quickly, under the direct influence of Anthony.”

Jo Vermaercke: “I was also introduced to Anthony and Thomas via the Belgian Co-Producer Laurent Hanon, with whom all three of us had previously worked together successfully. After my pleasant conversation with Vinterberg and Anthony, where we spoke about everything except the movie itself (laughs), I was contacted the week afterwards for a new interview. That’s when we watched the showreel. One week later I received the final call that I was onboard.”

To what extent did Anthony give you concrete directions when you started working together?

Patrick Otten: “You absolutely are given directions, but this lessens along the way because you start earning trust. Because we looked at each others rushes on the server, there was daily feedback from the day before and thus the trust growed with Anthony and also Thomas. Beforehand ADM had a clear vision and look for the movie. We are talking about a very specific movie. Director Thomas Vinterberg, who isn’t particularly known for creating movies full of spectacle, was therefore working somewhat out of his comfort zone. During the often complex and very technical briefings, Vinterberg was sometimes less on the foreground.”

Wim Michiels: “At the same time this made the difference in the movie. It isn’t an action movie per se but more an impressionist display of what happened back then, whereas the drama mainly plays out with the families of the characters. The urge to survive is the central theme and that’s when we are entering Vinterberg’s domain. The technical preparations were pretty heavy. There was a preparation of 10 production days, solely testing the camera underwater, which is a lot. This is as well as all the other necessary preparations. During this time, fellow workers could get to know each other and it is, similarly for Patrick, a question of earning trust. Anthony and Thomas provided lots of input, and everybody had to try to interpret this and turn it into something concrete. For me that meant deciding on the underwater look, thinking about possible lenses, lightsources, camera systems,… Everything had to be reviewed. Anthony wanted everything investigated in minute detail.”

Which camera system was eventually chosen for the underwater unit ?

Wim Michiels: “The choice was a full frame Camera of Canon that was set to, hold on, 44,000 ASA.”

Patrick Otten: “Because we were filming underwater and in the screenplay the final power drops out at a certain moment, the choice of an ultrasensitive camera was obvious. We also had to take into account the noise, the grain, that comes with such high ISO-values.”

Wim Michiels: “Anthony wanted to have that grainy look and feel for the movie. You have to imagine that all images were ‘denoised’ in post production, which is something of a real feat. The final result was more than successful. With a setting of 44,000 ASA, the camera didn’t have any latitude anymore, so the first underwater production day was frightening. Lighting up a small pocket torch underwater immediately produced extreme overexposure of light!”

Patrick Otten: “Anthony has developed a personal relationship with Canon Japan; in the past they already cooperated on projects. Anthony’s choice was a little box around the sensor with some connectors which only existed in EF-mount. For Wim, we looked for a solution to allow us to use the Cine-lenses and the possibility to fit a casing around it.”

Wim Michiels: “Coincidentally I had found a set of Leica lenses in UK. Afterwards it appeared that Patrick also had a set of leica lenses that fitted the camera casing/housing. Subsequently, we invested a lot of time in the camera casing/housing. Everything had to be able to communicate, all signals had to be read….an incredible techno-mechanical conundrum.”

Did you have to step out of your comfort zone during the production? How was the communication on set? What were your biggest personal challenges?

Wim Michiels: “I think that it was a huge challenge for many technicians that worked on this. Creating light underwater for 44,000 ASA is out of everyone’s comfort zone. Once we, as a camera department, had gained the trust of the Director and DOP, the work ran smoothly. We had a separate intercom system to communicate with each other during filming. Anthony gave more of a sense as to what the result had to be and mainly told stories to illustrate an atmosphere. Oddly enough, he rarely used technical language or camera-operating language. It was up to us to interpret the feeling correctly. If it was right, we were called out of the water to drink coffee together (laughs).”

Patrick Otten: “There wasn’t a single camera position where the camera wasn’t on sliders or didn’t move. The ship in the studio was able to lie on 4 or 5 water levels, and the hull was modular to allow space for the camera to move when necessary. The biggest challenge was the daily physical fight with water and fire, same for the cast. For the gaffer and key-grip there were just as many challenges.”

Wim Michiels: “I have, together with my wife, trained forty people (actors and stunt (wo)men) to work underwater. There were different categories, depending on the type of work that these co-workers had to undertake. Not everybody was suitable to carry out underwater stunts.”

Was there a time when all three of you stood on the set at the same time?

Wim Michiels: “Actually there were few sequences where all of us were involved in at the same time”

Patrick Otten: “All AED-studios (Lint) were taken up by this production. That meant there were different parallel sets that were being built or were filmed on simultaneously. We would send “playback” over to main unit and make adjustments based on feedback ”

What was the biggest difference compared to a Belgian production? Was the approach of a DOP on this set different than what you are used to?

Wim Michiels: “Interestingly every production day started at 7am and you spent a whole morning looking in great detail at how a scene could be executed , something that you rarely see on a Belgian production. The creative preparation process where Vinterberg and DOP give directions to a team of almost 100 people lasted until lunch. Only in the afternoon did the actual filming happen.”

Jo Vermaercke: “We had the feeling that our overtime started at the beginning of the day (laughs). We are used to arriving on the set, do a run-through with the Director and actors, and then start filming. Here it was the complete opposite. That’s also due to the strong personalities. Both Thomas and Anthony are very outspoken characters which you need to take into account and have to be able to get along.”

Patrick Otten: “On an average Belgian production you have less resources. Everybody works to get the maximum out of the resources and time that is available. I think there is more pressure from Production –side and the Assistant-Director to stay within those limits. On the set of Kursk there was still room to research, put things in question, to adjust, and improvise, something you don’t immediately expect with such a production.”

Wim Michiels: “With regards to my departement, I am very happy with the final result of the underwater scenes. This is a direct consequence of the ten preproduction days they had scheduled. That huge preparation just pays off and such luxury we rarely or never have on Belgian sets.”

Jo Vermaercke: “Because of the rigid structure of the enormous production machine, it wasn’t easy to get everyone in the same creative mindset. Time was really taken for this. Thomas sometimes filmed alternative versions of the same scene; another way to have choices during the edit. A luxury Thomas could afford, in part because of his strong position as Director. We aren’t talking about an ego, but about a clear vision, combined with a good dose of guts. That freedom of thought and creativity was remarkable.”

Wim Michiels: “You have to motivate your department to go along with it; everyone has to be focused on the end result. I had a big responsibility within the underwater team and that was an adjustment. Also, the form of communication was different than we’re used to, and was therefore a challenge.”

What have you learned personally on this project?

Patrick Otten: “I have gained different perspectives of stunt men. In particular, I learned that they aren’t necessarily good actors. You can put together the craziest action scenes, but if you are working with bunch of stunt men, you quickly notice that for some scenes you don’t achieve the desired level of acting performances. Technically everything can be perfect, but if you feel that they cannot meet the expectations in front of the lens, even under the management of Thomas and Anthony, that doesn’t make your job as second unit Director any easier!”

“ The biggest lesson I have learned from a project of this size is one in social engineering: how to deal with different personalities and characters with a certain service status. I encountered aspects that are inherent to a big structure, and were unknown to me before. I learned how to find my own place within it …For sure I also learned to accept that a large percentage of your work does not make the final cut”

Wim Michiels: “If a particular scene wasn’t good enough, it was simply removed even if it was worked on for days with tens of people. I remember a scene where the dininghal of the submarine submerged and tons of water flooded in, and Thomas said dryly: Is that it? (laughs). You knew then that scene wouldn’t make the cut. From the first day the bar was set very high.”

Jo Vermaercke: “I especially learned that on such a large production, the daily output is viewed differently. A large chunk of the material didn’t make the cut; more than 100 hours of material was reduced to 2 hours. For days we worked with a large crew on a big scene on a military ship in Toulon (FR), but that scene didn’t feature in the film.”

Patrick Otten: “I like to come back to the social engineering. It is actually a form of politics, of diplomacy, where you constantly have to anticipate or adjust to the larger picture. The stakes are much higher than what we are used to. It is a form of chess or stratego where every decision has grave consequences. You have to become accustomed to the hierarchy and the interplay between three strong personalities: the director, the DOP, and production designer (Thierry Flamand). Adjusting to the preferences of another DOP took getting used to but quickly it proved to be an enrichment.”

Wim Michiels: “The technological knowledge you have, that doesn’t get put into question, but the human aspect makes or breaks the cooperation on a set of such size. You have to also win over your department; everyone has to be focused on the end result.

Jo Vermaercke: “It helps if you have experience and are able to fit yourself into the structure of the large and complex whole. You get assigned a particular place where something very specific is expected of you. The challenge is then to add value to it.”

What type of technical setup was chosen?

Patrick Otten: “ Everything was filmed on Arri Alexa cameras with Canon K35-primes. For certain scenes rehoused Schneiders were used. Occasionally, a Flare-camera was prefered (a mini camera with a little sensor and C-mount lenses) which Anthony used on his set and with which he did crazy things. For the scenes in the bath I created a tailor-made underwater camera housing. This more industrial camera was ergonomically rebuilt by Anthony’s Swedish engineer-friend. That camera gives the opportunity to get very close, so the depth of field is smaller than what you would expect with this sort of camera. It is a kind of palm-camera that Anthony used on previous projects and it was put to use whenever he felt the need. For the underwater shots we had a Canon full frame camera with very high ISO-values. There were splash, crash, & underwater housings for all possible circumstances.”

Wim Michiels: “The connection Anthony had with the engineers of Canon Japan was an added value for the production. Specially for Anthony, they rebuilt that camera (for the underwater scenes) to a PL-mount which is pretty exclusive. On top of that, we just asked for a second one and got it (laughs). I think that for us, as modest Belgians, our main asset came in the form of our technical background and expertise.This way we made special soft light sources for particular scenes. The basin where filming took place was only 3.8 metres deep; we had to use very “thin” light sources to be able to light up from the bottom. We also let those same ultra low-intensity flatpanels float on the surface.”

Patrick Otten: “Anthony had, aside from his own look for the project , a system to apply a colour-differentiation in the lighting of each scene by using two contrasting and sometimes complementary colours. This allowed him to keep extra possibilities for the grade. We had a DIT on set who monitored exposure and settings and the (online) rushes came with a look in the right direction.”

Jo Vermaercke: “Everything was filmed on RAW because of the large CGI component of the movie, which meant there was huge amount of data. Everything was prepared into the finest detail and there was constant consultation between the VFX supervisor and the camera department. That way you know exactly what was needed for each scene.”

Wim Michiels: “The post-production process was also prepared until perfection and ran through multiple times in advance; nothing was left to chance. All the energy that was put into it was substantial.

What about the safety measures for such a complex film set?

Wim Michiels: “Considering we had to deal with high risk shots, this had an impact on the safety provisions and production insurance. We had certified gaffers specifically for the underwater shots at our disposal, a position that doesn’t exist in Belgium. Then you quickly have to deal with complex insurance questions that are pretty unfamiliar to us. We don’t have a tradition of implementing those insurance rules in great detail. There is still a lot of work to do for these sort of things!”

Jo Vermaercke: “Not only with underwater shots do you see this phenomenon, but we also notice this with rigging. Once you start working abroad, you work with certified people that are specially trained and hired on the basis of a risk analysis. In Belgium we do not have this, the safety culture is far from ingrained in Belgian film sets. To put it in a positive perspective, such a production helps us raise the safety norms for local productions.”

Wim Michiels: “For water and underwater shots this is simply a top priority. I was really glad that we could set our own safety measures for the underwater department because we had already built up experience for this in prior years. For this movie the production brought over extra people from England.”

DOP Anthony Dod Mantle on finding and working with his Belgian crew:

” Finding a crew on any production is a dangerous business. Not because there are not enough talented technicians around for hire .It is much more a case of a selecting the right crew of egos to serve together on a ship at sea …the common universal task is to steer the vessel through whatever tricky waters lie ahead …each individual artist or technician has to comprehend at a deeper level how irrelevant any demonstration of personal ‘talent “ is …compared to the humble willingness to collaborate together towards a higher mutual goal.

My first task is of course to find crew members who possess an adequate level of expertise as filmmakers….but after seconds on the phone and some moments sharing a showreel….I have that part of the matter well assessed and in place…The next deeper challenge and higher risk factor that can jeopardise the ultimate work flow of the team is if I fail to trust my instincts about the persona behind the CV’s…its almost like having to X-ray the attitude behind the shot maker…

I hunt down humility and integrity in the story tellers I choose …these qualities are essential to me .

Thomas and I have made many films together over the years ..and have broken the ice in public and in private a few times ..thus we can talk quite directly and without camouflage to one another .This can be quite public..and a little provocative to any bystander at times .But we are like this because we have learnt that any film is always bigger than any one ego….the more mentally settled and self contented my new team can be the better ..because they need to understand how hard sometimes it can be to struggle to maintain a vision and a cinematic cause . Kursk was no exception…it was a beast of a film to make with many unforeseen battles fought on the way .

Patrick Otten came to me via Laurent producer …and his twinkle of the eye dry sense of humour suggested to me that he could handle some eccentric tasks ….his experience was great and his approach off beat ..he had been spoilt by commercials and was hungry for fiction storytelling…so I trusted him on those grounds..because I understood that DNA . All honest cinematographers can understand this .He worked very hard for the film , at times on painstaking shots that first unit would never ever have had the chance to achieve.

Wim ‘Swim’ Michiels was the next to join the sinking ship.I saw his focus and methodology gene the moment he entered the room.Fundamentally professional and as deeply honest as his oxygen tanks could take him…he radiated an instant attention to the smallest of detail and was totally trustworthy and dedicated to doing only his best .His parameters for safety were admirable and the production should be totally thankful of this .

I knew that I would be introducing him to artistic ideas that were unconventional ,but I saw him listen as he wrapped his underwater frown around my words ….he always paid attention..and if he occasionally ever got frustrated or a little angry ..it would be a true indicator that something was wrong.I have never felt safer with an underwater camera..because he always listened ….to everything.

Last but not least Jo Steadycam Wermaercke , again top of the Laurent short list.In all honesty Jo was so obviously the first man that I should hire for this film..and yet he became the last to join us .. ..find the logic if you can!

Jo came to me at a time in his life that was far from easy …and I was deeply concerned that I should let him go for personal reasons that had absolutely nothing to do with his immaculate career and experience.He proved me wrong …it was more like recreation than work to share the scenes with him…as solid as a rock..focused ,and so open minded after so many years where habit can threaten to override spontaneous whims…but that never happened with Jo.

These were my Three musketeers yes ,and they were central to my approach to shooting Kursk. But, in all honesty …these characters can only be celebrated and thanked for their contribution to the visual language of Kursk on the ONE important condition that this article wraps these Musketeers firmly in the same life boat with Wim Temmerman and his team on lights and Dries Leerschool and his grip team…I shared and delegated through Wim and Dries to Jo ,Wim and Patrick…and without acknowledging this full creative equation..the drawings and sketches of production designer Thierry Flamand’s submarine would have never been transformed onto the cinema screen l , and the Kursk would never even have made it out to sea at all.

Thank you to all of you for an unforgettable Belgian Spring and Summer .”

Anthony Dod Mantle Asc.Bsc.Dff. was born on April 14, 1955 in Oxford, Oxfordshire, England. He is known for his work on Slumdog Millionaire (2008), 127 Hours (2010) and Antichrist(2009).

interview in cooperation with LOUIS VAN DE LEEST – PROJECT MANAGER MEDIARTE